US Department of Transportation

FHWA PlanWorks: Better Planning, Better Projects

| Key Decisions | Framework Applications |

|---|---|

Maricopa Regional Transportation Plan

Consensus Driven Effort to Balance Regional Needs

Executive Summary

With the City of Phoenix at its core, Maricopa County, Arizona is one of the fastest growing and most rapidly urbanizing counties in the nation. Sixty percent of Arizona’s 6.3 million residents live in the county. In recent decades, the transportation infrastructure of the region has struggled to keep pace with its tremendous growth in population and economic activity. High levels of congestion and long travel distances make transportation a top priority for all stakeholders in the region.

In 1985, Maricopa County entered into a unique arrangement to provide for the development of its freeway system. Under the leadership of the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) and the Maricopa Association of Governments (MAG), the region obtained approval from the state legislature to propose a half-cent sales tax to Maricopa County voters. Approved by the voters in October 1985, Proposition 300 authorized the sales tax to supplement traditional federal and state financing for the construction of the freeway system. Although the associated Long Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) encountered both funding and management problems in subsequent years, MAG and ADOT will complete the freeway system in 2008.

With the original sales tax due to expire in 2005 and the freeway system nearly complete, MAG needed to create a new transportation plan and to secure continued funding. Based on the results of various management audits and visioning efforts, MAG decided to broaden its decision-making process to increase stakeholder participation, accountability, and political buy-in. Accordingly, MAG established the Transportation Policy Committee (TPC) to guide the development of a new Regional Transportation Plan (RTP). The TPC’s 23 members include representatives from local governments, Indian tribes, ADOT, and the Citizen’s Transportation Oversight Committee (CTOC). In addition, the TPC includes six representatives from the business community. These representatives were crucial to maintaining unity among the TPC as well as generating support from outside the TPC. The TPC was the main decision-making body for the development of the RTP.

MAG developed the RTP in two phases. Phase I, from 2000-2002, included numerous background studies on the transportation needs of various sub-areas, corridors, and modes. Phase II, from 2002-2003, began with the establishment of the TPC. In Phase II the TPC developed the RTP document in a process that included the establishment of goals, assessment of needs, selection of performance measures, development and analysis of alternatives, and the creation of an implementation plan. MAG engaged the public in the development of the plan throughout both phases.

As with the 1985 plan, funding for the new RTP required the approval of both the state legislature and Maricopa County voters for its implementation. MAG’s allies in the business community were instrumental in passing HB 2292 in 2003 and HB 2456 in 2004. These bills placed the TPC in state law, outlined certain parameters of the development of the plan, and authorized the county election for the sales tax. Governor Janet Napolitano also approved the RTP by signing both bills into law. The business community was again instrumental in passing Proposition 400 in the November 2004 election, which extended the half-cent sales tax through 2025.

MAG successfully navigated a number of political challenges in developing the new RTP. The history of transportation planning in Maricopa County is highly politicized, with heavy involvement from both the state legislature and governors. The buy-in of all parties was essential to secure funding for the plan. In addition, competition between cities in the region threatened to undermine the plan. Different municipalities had different levels of need and different desires for their transportation systems. These challenges were made all the more pressing by the imminent expiration of the sales tax.

MAG responded to the challenges with both political tools and planning tools. The involvement of the business community was essential to the success of the plan. Business leaders served as liaisons between MAG, lawmakers, and the public. They were the glue that held the collaborative framework together. MAG also took an integrated regional approach to planning projects and allocating funds. The agency prioritized the regional agenda over competing local agendas as much as possible. This attitude helped to build political consensus. MAG also strove to make the plan as functional as possible. Key elements of the plan were a robust policy framework, performance measures for monitoring of the plan, and strong fiscal management practices. These aspects of the plan particularly helped to win the support of lawmakers and the public. As a result of MAG’s political and planning successes, the RTP dedicated a large proportion of funding for transit, against significant opposition.

As developed by MAG and approved by the state government and the voters of Maricopa County, the RTP is a comprehensive, long-range, multi-modal transportation plan that provides for the transportation needs of Maricopa County for the next 20 years. The plan represents a significant change in the region’s traditional patterns of transportation decision making and transportation investment.

Background

Maricopa County is the most populous county in Arizona, with nearly 3.8 million residents in 2006. The City of Phoenix sits at the heart of the county. In all, Maricopa County contains 25 incorporated cities and towns, five Native American communities, and substantial unincorporated land. It covers an area of 9,226 square miles. Sixty percent of the state’s population lives in Maricopa County.

The Maricopa Association of Governments (MAG) is the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) and the lead planning agency for the Phoenix urban area. The MAG Long Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) represents the federally mandated and fiscally constrained 20-year plan. The analysis area for the MPO covers all of Maricopa County as well as part of Pinal County. MAG is responsible for the development of the LRTP as well as the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) for the MPO region. In addition, the governor of Arizona has designated MAG as the principal planning agency for air quality, water quality and solid waste management. MAG is also tasked with developing population estimates and projections for Maricopa County.

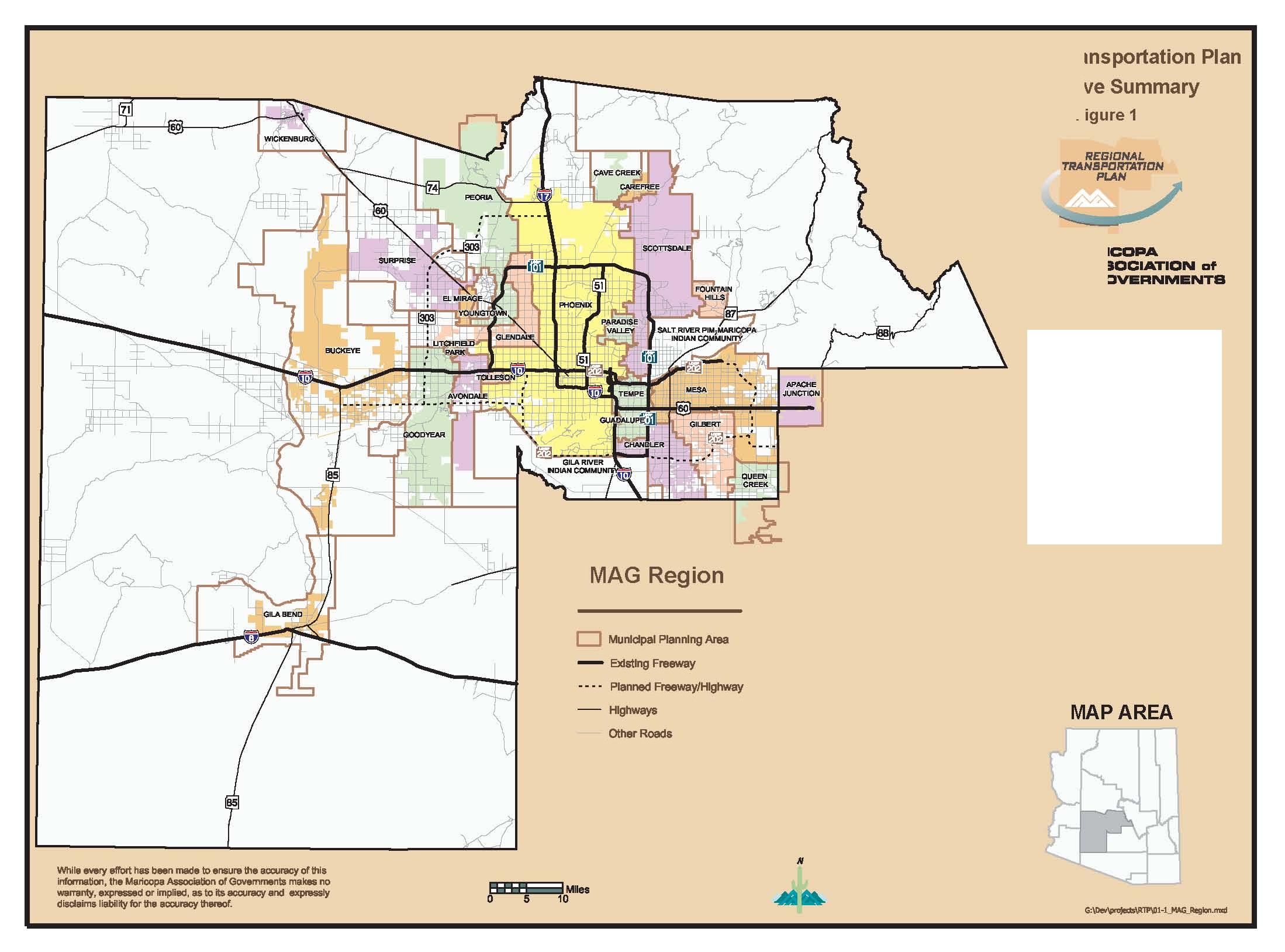

Figure 1. Map of Incorporated Areas of Maricopa County

Source: MAG RTP 2003, Executive Summary

For more than 20 years, transportation planning in Maricopa County has been heavily tied to funds from a half-cent sales tax on gasoline. The inadequacy of traditional state and federal transportation funds became apparent in the mid-1980s. At that time the MAG region was constructing its regional freeway system. A review of the 1983 Freeway / Expressway Plan indicated that projected levels of population growth would quickly overwhelm the planned additional capacity if constrained to federal interstate funds and state and city revenues. At the same time, Maricopa County citizens, frustrated with growing traffic problems, were identifying transportation as the metropolitan area’s major problem.

In response, MAG developed a new LRTP with an additional 161 miles of freeway, for a total of 233 miles of new freeway, in the 1985 Plan. ADOT, along with MAG and the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce, developed funding proposals for the new plan. State legislation passed in 1985 then allowed counties to propose excise taxes to the voters for use in transportation finance. Maricopa County voters passed Proposition 300 in October 1985. Prop 300 was expected to raise $5.8 billion over 20 years until it expired in 2005 but actually raised only $3.8 billion. All but $200 million of those transit funds were devoted to freeways and expressways.

The program ran into funding challenges in the late-1980s and early-1990s due to construction and right-of-way cost increases and revenue shortfalls. In 1994, MAG returned to the voters with two additional tax proposals to fund the revenue shortfalls. The voters rejected both proposals. The result reflected a lack of public confidence in the ability of MAG and ADOT to deliver the investment program.1 An initiative by Governor Symington and ADOT in 1995 reduced the planned system significantly and implemented a reduced scope for the remaining projects. The Governor’s Plan recommended deletion of certain corridors and corridor segments, proposed higher bonding levels and included corridor scope reductions to lighting, landscaping, structure widths and freeway lanes. In 1996, as a result of higher than anticipated revenues, MAG developed a revised plan that restored a number of the scope reductions implemented by Governor Symington and extended the program from 2005 to 2014 to allow the funding of two freeways that were removed the previous year. In 1999, MAG and ADOT, with the assistance of the state legislature and Governor Hull, provided new financing tools and accelerated the completion date of the program from 2014 to 2007. As a result, the last project of the regional freeway system outlined in the 1985 Plan is under construction and will be completed by mid-2008.

With implementation of the 1985 Plan approaching completion and the sales tax set to expire in 2005, MAG recognized the need for a new transportation vision with the required funding support to accomplish it. The agency began laying the groundwork for these efforts in 1999. To highlight_this this significant change, MAG renamed the LRTP as the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP), and the MAG Regional Council began to structure the policy committee that would guide the plan development.

Project Overview

MAG developed the RTP in two phases from 2000 to 2003. In Phase I, from 2000-2002, MAG conducted a number of background and technical studies on particular modes, geographic areas, and corridors. During this period, the MAG Regional Council created the policy framework for decision making. In Phase II of the process, from 2002-2003, MAG drafted the RTP in a prescribed process that included adoption of goals, assessment of needs, selection of performance measures, development and analysis of alternatives, and the creation of an implementation plan.

The RTP will channel $16 billion (2002 dollars) worth of funding into the region’s transportation infrastructure over the next 20 years. Major components of the plan include the addition of capacity on existing freeways, new freeways, a new light rail system, an expanded and enhanced bus system, and upgrades to arterials. Figure 2 below provides a breakdown of total regional funds dedicated to each investment category.

Figure 2. Breakdown of Regional Funds in MAG RTP

The plan meets the transportation needs of the region as a whole while balancing the individual needs of sub-regions and cities. The RTP has the support of all stakeholders who engaged in the process. MAG is currently updating the financial element of the RTP, along with some of the technical information, on an annual basis. Goals, objectives, and the prioritization of projects within the plan generally do not change.

Project Drivers

Whereas Maricopa County once supported an almost exclusively car-based transportation system in the past, new development and demographic factors require that the region consider transit service and other alternative mode options, in addition to highway capacity solutions.

MAG developed the RTP to build public support and regional consensus in order to renew a countywide sales tax to fund transportation infrastructure. The original half-cent sales tax, approved by Maricopa voters in 1985, established a 20-year funding plan for building new freeways. The imminent expiration of the tax forced public officials to reconsider the transportation investment and funding plans for the county.

The MAG region is one of the fastest growing regions in the nation. From 1990 to 2000, Maricopa County experienced population growth of 44 percent, from 2.1 million people to 3.1 million people. This extraordinary rate of population growth brought rapid changes in land use and in pressures on the transportation system. Continued high population growth is projected for the next 30 years. As a result, Maricopa County must remain proactive in transportation planning and investment. Without a forward-looking planning approach, such high growth rates could easily overwhelm the region’s transportation infrastructure.

In addition to rapid growth in population, vehicles, and developed land, the nature of the region has also shifted. Traditional fringe development patterns in the region are now accompanied by infill development patterns in central areas. Increases in ethnic minorities, seniors, and low income populations are also changing the demographic structure of the area. Whereas Maricopa County once supported an almost exclusively car-based transportation system in the past, these new development and demographic factors require that the region consider transit service and other alternative mode options, in addition to highway capacity solutions.

Initial Planning Approach

Maricopa County struggled with planning and implementation issues for its transportation system throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Local, regional, and state agencies all participated in the planning process to different degrees. As a result, questions of governance and funding of the transportation system have become one of the chief political concerns of both Maricopa County and the State of Arizona.

At the state level, Governor Hull established the Transportation Vision 21 Task Force in February 1999. The Task Force was intended to “evaluate existing processes, resources and infrastructures” and “recommend planning and funding strategies for Arizona’s multimodal transportation future.”2 The recommendations of the Task Force included the reform of planning and programming processes, the enhancement of accountability and responsiveness of the transportation system, the establishment of a 20-year statewide transportation system “budget,” and the establishment of clear funding priorities.3 One specific recommendation was that the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors serve as the interim or possibly permanent transportation district for Maricopa County. The state legislature adopted this recommendation as HB 2288. The measure was opposed by MAG and was not implemented.

At the same time, MAG had begun to consider the renewal of its own LRTP. In early 2001, the MAG Regional Council began discussions about restructuring the decision-making framework of the MPO. MAG formed the Regional Governance Task Force and Regional Governance Advisory Committee to fully explore options for including all regional partners in the transportation decision-making process. Collectively, the groups met more than 27 times to clearly identify roles and responsibilities for a public-private partnership to develop the 2003 RTP. As a result of these meetings, the Governance Task Force “determined that MAG needed to be more inclusive” in its decision making.4 Accordingly, MAG formed a new RTP guidance committee, the Transportation Policy Committee (TPC), comprised of “twenty-three members, including a cross-section of MAG member agencies, community business representatives, and representatives from transit, freight, the Citizens Transportation Oversight Committee and ADOT.”5 The MAG Regional Council appointed the TPC in July of 2002. By this time, background studies to inform the development of the RTP had already begun. The TPC became the primary decision-making body guiding plan development.

Major Project Issues

The development of the RTP faced several political issues. The most pressing issue was the potential loss of the sales tax revenue. The tax approved by voters in 1985 would expire on December 31, 2005. Voters would have to approve a new tax by the end of 2005 to avoid losing this important revenue source. This firm deadline provided the incentive to work aggressively to produce a regional plan in 2003. MAG and its allies could then demonstrate first to the legislature and second to the voters that the RTP would meet the transportation needs of Maricopa County for 20 years.

Another issue in the planning effort was providing equity within the region. Transportation infrastructure is particularly important to the MAG region because of its dispersed development and travel patterns. Citizen polls routinely find that transportation is one of their top concerns. As in most areas of the country, there are insufficient funds to meet the region’s transportation needs. This lack of funds results in competition between jurisdictions or sub-areas in a metropolitan region.

Maricopa’s urban core lies in the central and eastern portions of the county; however, the area west of Phoenix (the West Valley) has been steadily gaining population and is recognized as a future growth area. This dynamic created different priorities across the region. More developed areas were interested in high capacity transit, whereas less developed areas were interested in new freeways. Ultimately, the TPC was able to construct a plan that provides support for both highway and transit needs and that balances the need of individual jurisdictions with the needs of the region.

A third issue for the RTP effort was the visibility of transportation planning and programming in Arizona at all levels of government. The past 20 years have seen ongoing involvement in the transportation decisions of Maricopa County by several governors and legislatures. During the development of the RTP, the Business Coalition lobbied for the sales tax option against strong resistance in the legislature and well-financed opposition to the light rail component. Because the RTP is funded largely through a sales tax, there is an ongoing requirement for monitoring at the legislative level. This high-level political focus on transportation could be very disruptive to the planning process if the region were subject to political upheaval.

Institutional Framework for Decision Making

The institutional framework that produced the RTP is complex and multi-faceted, involving all types of stakeholders from the local to the state level. An internal framework made key decisions about the development of the plan and produced the RTP document. An external framework, linked to the internal one largely by the business community, authorized and prescribed plan development and provided for its eventual implementation.

The TPC, established in 2002, is the result of an effort by the MAG Regional Council to broaden the decision-making process, and particularly to increase the participation of the commercial sector. Business representatives are included by appointment of the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House.

Internal Framework

A group of local and regional government agencies, along with members of the business community, formed the core of the decision-making structure for the development of the RTP document. As the designated MPO, MAG led decision making. MAG’s Transportation Policy Committee (TPC) was the primary decision-making body.

MAG Structure

The Regional Council is the main governing and policy-making body of MAG. It is composed of one elected official from each member agency, who is typically the mayor, chair of the Board of Supervisors, or governor or president (in the case of Indian Nations). The State Transportation Board members for Maricopa County represent ADOT on the Regional Council. The chair of the Citizen’s Transportation Oversight Committee (CTOC) represents the region’s citizens. As the MPO’s formal policy committee, the MAG Regional Council adopts the RTP.

The Transportation Policy Committee (TPC) is the transportation sub-committee within MAG and the primary advisory committee for the RTP. The TPC, established in 2002, is the result of an effort by the MAG Regional Council to broaden the decision-making process, and particularly to increase the participation of the commercial sector. The TPC is composed of 23 members, including local government officials, private sector representatives, one representative from the Native American Indian community, one State Transportation Board member and the Chair of the CTOC. The six representatives from the private sector are appointed by the President of the Senate and Speaker of the House and serve six-year terms. Elected officials serve a two-year term, and are selected by specific guidance to provide representation for all jurisdictions in the area. The role of the TPC is to help develop regional transportation policy positions for the MAG Regional Council to consider. This committee further provides oversight for the implementation of Proposition 400. Specific responsibilities of the TPC include: 6

- Regional Transportation Plan

- Transportation Improvement Program

- Amendments to the Transportation Improvement Program

- Material cost changes to the Regional Freeway Program

- Accelerations to the Regional Freeway Program

- Amendments to the Regional Transportation Plan

The TPC meets monthly to review inputs from the MAG staff and its consultants.

MAG-ADOT Relationship

As the owner-operator of the state transportation system, ADOT was an important stakeholder in the development of the RTP. In addition to having representatives on both the TPC and the MAG Regional Council, ADOT has a close working relationship with MAG. The level of interagency collaboration is unusual for a state DOT and an MPO. In fact, MAG and ADOT shared planning staff in the early years of the Phoenix area MPO. The planning division of MAG left ADOT in the early 1990s, but still provides transportation planning services for ADOT in the MAG region.

In 1999, as part of a statewide agreement among transportation professionals referred to as the Casa Grande Accords, MAG and ADOT made a formal agreement to cooperate in the planning and programming of highway projects in Maricopa County. The principles of this relationship are: 7

- One multi-modal Transportation Planning Process that is seamless to the public;

- Encourage early and frequent public and stakeholder participation;

- Objectives of the state, region and local plans will form the foundation of the Statewide Long Range Plan;

- Plan and programs will be based on clearly defined information and assumptions; and

- Programmed projects linked to Long Range Transportation Plan objectives to ensure equitable allocation of resources.

The relationship between ADOT and MAG is one of seamless cooperation. In addition to its formal participation in MAG committees as well as the Regional Council, ADOT also participates in the development of the RTP through its strong working relationship with MAG. The selection of projects to fund is made in the planning phase through discussion between ADOT and MAG. Specific projects come to ADOT from MAG with commentary, traffic analysis, and air quality analysis to support funding decisions. ADOT controls the environmental review process with MAG approval of the EIS and inclusion of the project in their TIP. The relationship between MAG and ADOT is formalized in legislation.

Other Stakeholders’ Involvement

The Regional Public Transportation Authority (RPTA) supported the development of the RTP. Although it did not have a specific representative on the TPC, a number of RPTA Board members were members of the TPC. The agency developed the initial transit plan that was used in the development of the RTP. In addition, state legislation required the RPTA to review the plan and issue written recommendations to the TPC at key points in the later stages of plan development.

State legislation also required the State Transportation Board and the County Board of Supervisors to issue written recommendations to the TPC. Indian communities and cities and towns had the option to do so as well. The legislation required the TPC to vote on the recommendations of these groups and issue a written explanation of its responses.

The Citizen’s Transportation Oversight Committee (CTOC) was involved in the development of the plan through positions on both the MAG Regional Council and the TPC. HB 2342 established the CTOC in 1994 in order to address the management procedures associated with funding problems for the 1985 plan; HB 2172 modified the committee structure in 1996. Although it has no true decision-making authority, the CTOC provides review and advisory functions for regional transportation planning in Maricopa County. The CTOC is comprised of one appointee from each of the five members of the County Board of Supervisors and two members appointed by the governor, including the chairperson. The CTOC interacts directly with both MAG and ADOT. CTOC members sit on committees within both of these agencies. The CTOC provides an official avenue for public access to the planning process, and acts as a watchdog to the transportation process.

The general public was involved in decision making through an elaborate public outreach process. The MAG Public Involvement Team coordinated the outreach process with the help of a public involvement consultant. Public outreach began in 2001 in Phase I of the RTP and continued through the final draft of the RTP. During the entire process, MAG held 150 public input opportunities, including expert panel forums, focus groups, special events, public meetings, hearings, workshops, small group presentations, and a MAG town hall. MAG also collected public feedback through a dedicated website and telephone polls, and received feedback via phone, email, and U.S. Mail. Events were both informational and interactive. In one series of workshops, citizens participated in an exercise in which they developed their own fiscally constrained plans. The engagement of the public was a guiding principle for both MAG and ADOT.

Figure 3 below portrays the internal decision-making structure for the development of the RTP document. The TPC was responsible for the step-by-step development of the plan. The MAG Regional Council ultimately approved and adopted the plan. The TPC exchanged information with and solicited feedback from other groups throughout the development of the plan. The solid line to stakeholder agencies indicates feedback mechanisms that were formalized by law. Most of these organizations also had representation on the TPC. The dashed line indicates a structured, but not legislatively prescribed, flow of information and feedback between the TPC and general public. Ultimately, many more parties were involved in the passage of the state and county legislation that have enabled the implementation of the plan. These parties are described within the external framework below.

Figure 3. RTP Decision-making Structure

External Framework

The external decision-making framework worked at the legislative level to authorize and fund the RTP. The primary players were the business community, the state legislature, and the public; but all parties involved in the internal framework also played a role.

Area business leaders were involved in the development of the RTP and passage of the sales tax measure in several ways. The Greater Phoenix Business Leadership Coalition (the Business Coalition) formed in November 2001. Comprised of 10 regional business leadership organizations, the Business Coalition promotes the economic health of the region. One of the Business Coalition’s key priorities, determined in 2002, was to support the extension of the half-cent transportation sales tax. This priority was formalized as Maricopa 2020.

Maricopa 2020 was a campaign effort heavily supported by the Business Coalition and the wider business community. Initiated in 2003, the campaign lobbied the legislature in support of several bills that authorized the RTP process including the formation of the TPC and the county election to extend the sales tax. The graphic below represented the Maricopa 2020 campaign. Once Proposition 400, the measure to extend the tax, was placed on the November 2004 ballot, the campaign renamed itself Yes on 400 and promoted the measure to the citizens. The six representatives of private industry on the TPC linked these campaign efforts and the Business Coalition to the internal framework. These members provided the commercial perspective at key decision points in the development of the RTP and ensured the business community’s interest in promoting the plan to voters.

The state legislature played a key role in the process by authorizing Maricopa County to hold a referendum to extend its half-cent sales tax. HB 2292, signed into law on May 14, 2003, codified much of the RTP decision-making framework and process. It also made MAG accountable to the state legislature in the development of the RTP. Specifically, the bill:8

The state legislature played a key role in the process by authorizing Maricopa County to hold a referendum to extend its half-cent sales tax. HB 2292, signed into law on May 14, 2003, codified much of the RTP decision-making framework and process. It also made MAG accountable to the state legislature in the development of the RTP. Specifically, the bill:8

- Recognized the role of the TPC in developing the RTP;

- Allowed a county election to extend the half-cent sales tax;

- Required the TPC to cooperate with ADOT and the RPTA in the development of the plan;

- Established consultation processes for key stakeholder groups;

- Mandated regular budget updates by ADOT and RPTA to ensure project costs do not exceed revenues;

- Required MAG to report annually on the progress of the Plan and established a procedure for plan amendments; and

- Expanded the purview of the Citizen’s Transportation Oversight Committee (COTC) to include all projects in the RTP.

Governor Janet Napolitano signed the bill into law.

The general public was also an important decision maker. With the authority to approve or deny funding for the RTP in the referendum, the voters made the final decision on the development of the region’s transportation infrastructure. In Proposition 400, voters approved both designated funding proportions for different modes and a list of actual projects. The public’s involvement in the internal decision-making structure was crucial to their eventual approval of the plan.

These types of cross-linkages among decision makers contributed to a strong collaborative base in the institutional decision-making framework.

Transportation Decision-making Process / Key Decisions

The decision-making process that produced and implemented the MAG RTP included both the development of the RTP document, guided internally by MAG, and the authorization of the RTP concept and funding. The latter played out largely between the state legislature and a campaign effort lead by the business community, MAG, and other key stakeholders.

MAG developed the RTP in two phases. Phase I, from 2000-2002, consisted of background and technical studies on particular modes, geographic areas, and corridors. MAG consulted with stakeholders and the general public throughout the development of these studies. In Phase II, from 2002-2003, MAG developed the RTP in a prescribed process that included adoption of goals, assessment of needs, selection of performance measures, development and analysis of alternatives, and the creation of an implementation plan. The TPC guided the process throughout Phase II of the plan’s development. MAG conducted outreach activities to participating agencies, stakeholder groups, and the general public throughout Phase II. Studies and public input opportunities conducted during Phase I informed the development of the plan as well.

The TPC began their work on September 21, 2002, with a day-long retreat to establish a consistent understanding of principles as well as identify issues and concerns. MAG staff provided the technical understanding of the planning progress and responded to specific questions from the policy makers. MAG staff requested all TPC members to submit “Things I Know” and “Things I Need to Know” about transportation. MAG devoted considerable time to a discussion of air quality conformity and its impact on the RTP. From this forum several principles emerged that would guide the development of the plan through the following 15 months:

- Reliance on local plans and strong public involvement

- Create a plan that includes both highway and transit options

- Clear identification of funding resources and its ability to meet the needs

- Transportation and land use must be linked

The TPC was clear that the “plan needs to reflect citizen needs and what they want.”9

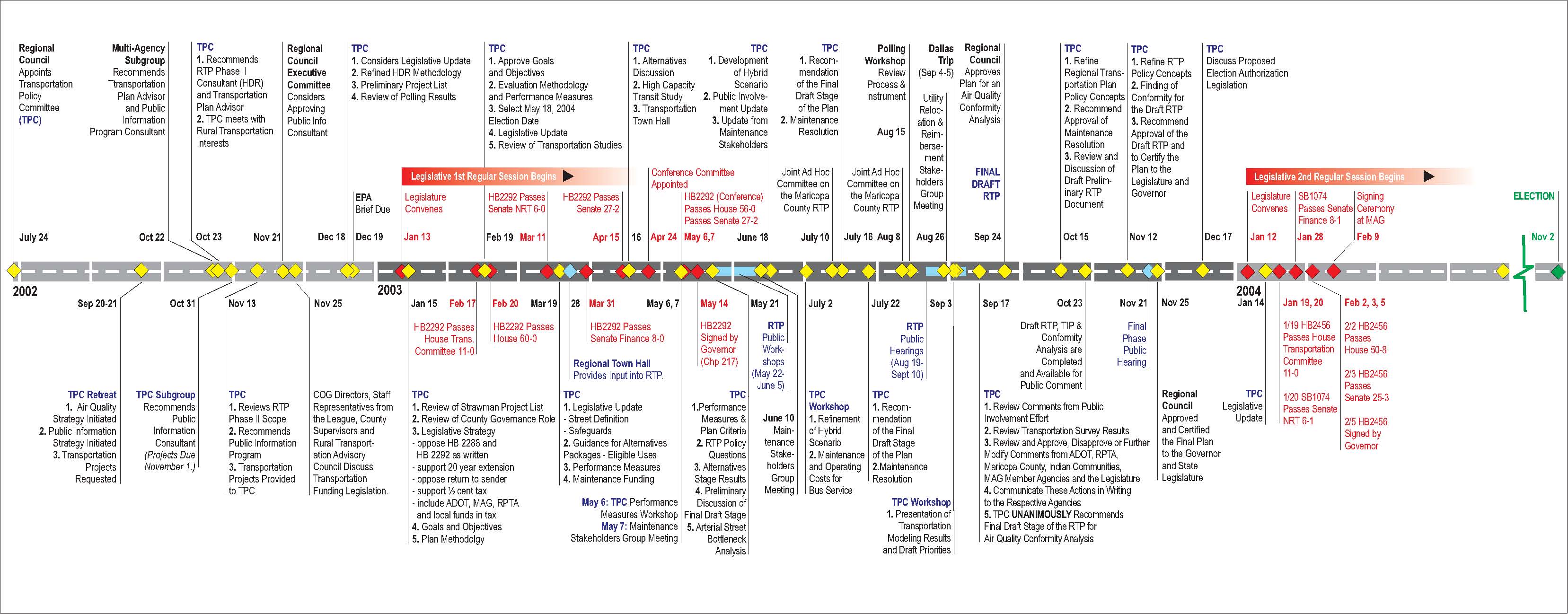

Figure 4 below diagrams the technical methodology used to develop the final plan scenario. The TPC followed the steps outlined here in rough chronological order. Appendix A provides a more detailed timeline of TPC and other stakeholder activities from July 2002 to November 2004.

Establish Goals, Objectives and Performance Measures

The RTP is being developed through a detailed, comprehensive process that focuses on performance-based planning. This includes the development of a solid policy foundation for future transportation infrastructure decisions.

-Transportation Modeling Scenarios Draft Report

The TPC established goals, objectives and performance measures for the RTP over a series of meetings and workshops from January to May 2003. Previous efforts from Phase I informed the development of these elements. Five expert panel forums and 16 focus group sessions were held in the region in 2001. In addition, a historical document search drew goals and objectives from the planning documents of member agencies. Input from other MAG committees, other studies, and extensive TPC discussions also provided assistance in developing goals and objectives.10 Goals were based on an over-arching vision for transportation in the region. Objectives that are more specific supported each of the goals.

Figure 4. Plan Development Process (Phase II)

Source: Regional Transportation Plan, Figure 6.1

The TPC approved a set of goals and objectives at its meeting on February 19, 2003. The four goals were:

- System Preservation and Safety

- Access and Mobility

- Sustaining the Environment

- Accountability and Planning

Performance measures were one of the most important elements of the plan politically. Legislation that allowed the 1985 sales tax included the requirement for audits every five years, and these audits proved valuable in making plan adjustments. MAG anticipated any reauthorization legislation to follow this example. Performance measures provided quantifiable assessment tools that were linked to goals and objectives. In addition, evaluation criteria related specifically to the quality of the plan as a governance tool. The TPC approved performance measures for each objective at its meeting on May 21, 2003. In all, the RTP contains four goals, 15 objectives, 19 performance measures, and five evaluation criteria.

Identify Needs and Deficiencies

A rigorous technical review of regional transportation deficiencies and recommended improvements enhanced the policy foundation for the RTP. MAG staff conducted the review with the help of a consultant. Corridor assessments, mode-specific analyses, and other regional planning studies helped to identify deficiencies. The TPC also considered projects identified by MAG member agencies. These collection exercises yielded an initial list of 400-500 projects. The unconstrained cost of all of these projects was estimated at $20-30 billion. The final plan cost is $15.8 billion.

Determine Alternative Plan Scenarios

To develop alternative plan scenarios, MAG proposed guidelines for the allocation of funds to projects. Considerations included the types of projects that could be funded and whether the sales tax should be restricted to capital costs or include operations and maintenance. In the April 2003 meeting of the TPC, MAG staff presented the major assumptions used to develop the initial scenarios. The assumptions provided a consistent basis for analysis of projects across scenarios. The assumptions were:

- Local contributions for 20 percent of capital costs for arterial street projects;

- All maintenance costs for arterial streets paid from local funds; Fifty percent local contribution for new traffic interchanges;

- All other freeway improvements paid from regional funds;

- Current local contribution for bus services will continue, adjusted for population growth.

- Funding for the 20-mile light rail transit starter segment and for 10 miles of LRT extensions from local and FTA 5309 funds;

- Fifty percent of operating costs for expanded local bus service paid from local sources;

- Twenty percent local contribution for capital costs for additional express bus, bus rapid transit and rail; and

- Regional funds for all operating costs for additional express bus, bus rapid transit, and rail.11

MAG grouped the long list of projects into three scenarios for analysis. By this stage, the TPC had eliminated some of the projects based on an initial benefit-cost analysis, but most of the original projects were included in at least one of the three scenarios. All three scenarios contained a core group of projects, including pre-committed projects and major freeways. Each of the three scenarios emphasized a different modal alternative. The three scenarios were:

- Scenario A: Higher Freeway Emphasis

- Scenario B: Higher Arterial Street Emphasis

- Scenario C: Higher Transit Emphasis

MAG particularly emphasized public involvement in the drafting of alternatives for the plan. During May and June 2003, MAG held a series of public workshops throughout the region at which participants were given the opportunity to develop their own fiscally constrained regional transportation plans. Participants then formed small groups and developed a consensus on spending priorities for the transportation system. The output of these workshops informed the spending priorities for the RTP. TPC meeting minutes indicate that the funding priorities survey “showed support for new freeways, but at lower funding levels; support for improving the existing system; minimal support for HOV lanes; and strong support for freeway maintenance. [Ms. Gunn] summarized the transit funding findings. She noted that support was strong for commuter rail, with respondents allocating more than allowed for this mode.”12

Evaluate Scenarios

MAG analyzed the three scenarios using the regional travel demand model, which includes a transit component. In addition, detailed data available in the RPTA plan supported a robust analysis of the transit components. MAG’s modeling capabilities are seen as a particular strength of the MPO, and there was little to no disagreement on the evaluation component. As stated by a TPC member, “This region is lucky to have a regional planning agency that has one transportation model, does population projections, travel demand, emissions, and air quality modeling under one roof.”

Evaluation of the three scenarios highlight_thised the most effective projects in each of the modal categories. The performance measures approved by the TPC provided the framework for evaluation of the scenarios. The performance measures showed the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches to meeting the region’s transportation needs.

Formulate Hybrid Scenario

In May 2003, the TPC discussed the three alternative scenarios. In accordance with HB 2292, MAG gave ADOT, Maricopa County, and RPTA 30 days to review the scenarios. These agencies could comment on, approve, disapprove, or modify the scenarios. MAG staff used the input from these reviews along with comments submitted by TPC members to draft a hybrid scenario, presented at the June 18, 2003 meeting. The TPC refined the hybrid scenario at their meeting on July 2, 2003. The hybrid scenario became the Final Draft Stage scenario, which was the basis for plan adoption.13 The TPC adopted the Final Draft of the RTP on July 22, 2003.

MAG collected input on the Final Draft of the RTP in six additional public meetings and six meetings with the business community specifically. Each meeting included an open house, a presentation on the RTP, and a question and answer period.

Phasing and Funding

The Final Draft Stage of the plan considered both the funding and the phasing of projects in the plan. MAG prioritized projects chronologically based on revenue streams, project readiness, and need as determined by traffic volumes, congestion, and system continuity. The TPC allocated the projects to five-year phasing blocks.

The final funding breakdown for the RTP allocated 57 percent of total regional funds to freeways and highways, 32 percent to transit (15 percent bus, 15 percent rail, two percent other transit), nine percent for street improvements, and two percent for other programs (including safety, bicycle, pedestrian, and ride-sharing).

On September 17, 2003, the TPC voted to recommend the Draft RTP to the MAG Regional Council for an air quality conformity analysis. The Regional Council then approved the plan for analysis. After some final revision of the plan and associated policy concepts by the TPC, the Regional Council approved the Final Plan on November 25, 2003.

The final adopted plan strategy represents a sharing of resources to accomplish the goals of all stakeholders. Rather than a sub-allocation type of funding approach in which jurisdictions or regions are given “their fair share” of the resources, the policy guidance provided the basis for the distribution of funding according to goals set by the TPC. The establishment of specific goals and objectives toward transit supportive development required that funding was allocated toward this need. The result was an RTP with the following components:

- New and improved freeways with better access and more capacity

- More transportation choices

- Improved streets and intersections to help relieve congestion

- Expanded commuter options for easier rush-hour travel

- Extensions to the planned light rail system

- More bus service with less waiting

Legislative Process

“If you try to create the formula before the plan, you put the tax in jeopardy. We need to let voters know the good that has been done regionally. We need to stay together. The plan will create the equity.”

After approval by the MAG Regional Council, the RTP still required approval by the state legislature, the governor, and the voters of Maricopa County.

HB 2292 codified the structure of the TPC and provided Maricopa County the ability to place the sales tax extension on the ballot subject to a subsequent review and authorization to move forward from the legislature. HB 2292 also continued the participation of the legislature in two important ways. First it required that the legislature and the governor certify the RTP before the election for the sales tax. Secondly, it provided the legislature a means for ongoing oversight of the RTP through regular monitoring of the adopted goals, objectives, and performance measures. This level of legislative involvement in an MPO long range plan is rare, if not unprecedented.

The state legislature considered the MAG RTP beginning in January 2004. With heavy support from Maricopa 2020 and the Business Coalition, the legislature passed HB 2456 in February 2004. The bill certified the RTP and added additional stipulations about plan updates, management, and monitoring. Governor Napolitano signed the bill into law on February 5, 2004.

One specific provision of HB 2456 required MAG to adopt a “life-cycle” budget process for major arterial streets and intersection improvements. This process parallels one established by ADOT for the regional freeway system in response to budget problems with the 1985 LRTP. The life-cycle program forecasts and allocates funds through the full life of a major funding source. It requires regular updates to the fiscal element of the transportation plan to take account of shifts in projected revenues and costs. The intention of the process is that the agencies report regularly on changes in revenues and costs and address changes as they arise in order to ensure the long term fiscal viability of the plan. HB 2292, HB 2456, and Proposition 400 required similar budget assessments for ADOT, RPTA, and MAG. These life cycle assessments inform annual updates of the financial element of the RTP.

On November 2, 2004, the voters of Maricopa County approved the half-cent sales tax by a margin of 58 to 42 percent. This action authorized the primary source of funding for the implementation of the MAG RTP. It also constituted a rare exercise of decision-making power by the general public.

Lessons Learned

The MAG RTP successfully delivered a balanced, consensus-driven, long-range transportation plan for a region in which transportation is a top political priority. The leaders of the plan built on experience from past transportation planning efforts. They generated broad support across many stakeholder groups and crafted a plan that is innovative in its founding principles as well as in its principles of management. The experience of the MAG RTP offers a number of insights on success factors and key innovations to similar planning efforts.

Success Factors

Strong and Effective Policy Guidance

A strong policy framework is a defining feature of the MAG process. The process begins with the establishment of policy and then follows with coordinated implementation strategies and performance measures. Although policy decisions are the first step in any established planning process, many regions give little in-depth consideration to the relationship between goals and objectives and actual transportation improvement projects. The involvement of state-level policy makers also contributes to a strong policy framework.

The MAG RTP establishes specific policy goals and sets performance measures to provide feedback on their implementation. This step provides quantitative means to evaluate often qualitative standards.

The adoption of policies by consensus is often the most difficult step in the development of a regional transportation plan. For this reason, urban areas often establish very high level goals that all stakeholders can easily support. In contrast, the MAG RTP establishes specific policy goals and sets performance measures to provide feedback on their implementation. This step provides quantitative means to evaluate often qualitative standards.

The broad makeup of the TPC brought a variety of perspectives and a vast depth of knowledge to the policy-making process. Throughout the deliberations to craft the RTP, the TPC held in-depth discussions about the intricacies of allocating tax resources and about detailed issues such as the inclusion of operating and maintenance costs and the participation of developers in mitigation costs. The MAG staff and its consultants supported these discussions with clear and detailed technical information. The partnership between staff and policy makers respected the role of each in a supportive, seamless way. The pre-established schedule to meet the air quality conformity deadline and the expiration of the sales tax kept the deliberations ongoing and efficient.

Other MAG committees and sub-committees also gave special attention to setting effective policies. For example, the MAG ITS Committee established a sub-committee for regional transportation operations. This sub-committee report begins with a statement of vision and established principles followed by stakeholder involvement to assess the current traffic operations performance. From this point the group established specific measurable goals for a three-year and five-year timeframe.

The strong policy framework of the RTP has prevented the process from bowing to special interests and political manipulation. The framework prevented one attempt to earmark funds for an individual sub-area of the county. In another instance, the TPC protected the needs of a sub-area whose ability to generate revenue is far less than their need by distributing available funds in a more equitable manner. This regional perspective has built trust and collaboration among the member governments at the policy making level.

Arizona is unique in the level of involvement of the highest state elected officials in a regional planning process. Several governors have had a role in establishing the context for transportation planning through direct involvement in both land use and transportation issues. In 1995, when the Regional Freeway Program was in jeopardy due to high construction costs and lower than anticipated revenues, Governor Symington presented a plan that reduced the number of miles of new freeways to be constructed and reduced the scope of the projects that remained in the plan. During the early years of RTP development, Governor Hull established criteria related to transportation, land use, and conservation. Most recently Governor Napolitano has established a growth cabinet and has launched another initiative to integrate land use planning and infrastructure planning. In addition, recently enacted Growing Smarter legislation requires developers to consider land use and transportation together in large parcel developments.

The Arizona Legislature represents another high level of policy involvement in the RTP. After passing the enabling legislation for a ballot initiative, the legislature insisted on certifying the RTP before it allowed the election.

Effective policymaking is defined by a high level of buy-in and a structured implementation system. The MAG process displayed both of these qualities.

Performance Measures

As a specific tool for the monitoring of policy goals, performance measures are an important feature of the RTP. The performance measurements allow adjustments to be considered as well as to demonstrate plan success to the Arizona State Legislature. Regular performance audits required by the legislature have occurred since the 1985 plan. This level of oversight and accountability has prompted revisions to the plan strategy so that progress continues. Figure 5 provides an excerpt of the plan’s goals, objectives, and performance measures.

Performance measures identified in the RTP go beyond the traditional authority of the TPC. For example, Objective 3B relates to land use planning, but the transportation planning agency cannot dictate land use patterns. Still, transportation infrastructure is able to influence and respond to land use patterns. Indeed, the implementation of the RTP is already helping to accomplish this goal. The current construction of the light rail system is fostering the rise of transit-oriented development in the Phoenix area. In this way the TPC used performance measures to make the RTP as comprehensive as possible.

In addition to reinforcing the policy framework of the plan, the inclusion of performance measures and evaluation criteria was also crucial to getting the approval of the legislature and the public.

Public Engagement

The engagement of the public was vital to the success of the RTP because funding for the implementation of the plan depended on a countywide referendum. As the ultimate decision makers in this context, the voters had to understand and embrace the plan as developed. After a lapse in the public’s faith in MAG and ADOT due to a failure to fully deliver the 1985 plan on schedule and within budget, the agency put appropriate emphasis on the generation of public support. True to its stated principles, MAG initiated public involvement early in the process, kept the citizenry informed of progress, and invited feedback. Public outreach began in 2001 during Phase I of the RTP, before development of the document actually began. In Phase II, MAG focused its efforts specifically on intensive public outreach during the development of alternatives and on the communication of plan elements in advance of the election. The agency had a designated staff member in charge of the public outreach process.

Figure 5. Excerpt from RTP Goals

Source: Regional Transportation Plan, Chapter 4

The Maricopa 2020/Yes on 400 campaign was an instrumental ally to MAG in the field of public relations. Maricopa 2020 conducted polling of the general populace to determine their attitudes and preferences on transportation infrastructure investment and shared the results with MAG. It presented the plan to the public as a consensus-based effort with broad political support. The success of the Yes on 400 campaign provided funding for the plan.

Key Innovations

In addition to traditional success factors, a number of innovations characterized the MAG process. These included the establishment of a strong partnership with private industry, substantial funding for transit, and a regionally integrated perspective among policy makers.

Private Partnership Support

A major difference in the TPC structure from the traditional decision-making framework for long range transportation plans is the addition of six members from the business community. This change reflected the strong contribution made by the business leaders in the 1985 campaign for Proposition 300 (the original sales tax referendum); however, the benefits of support from the business community have gone far beyond the passage of the voter referendum.

The six members of the TPC from the private sector represent a diversity of transportation, land use, and business development interests. This addition to the public official leadership of the region provides credibility to decision making by inhibiting the forming of alliances toward special interests. In addition, the business members have the ability to act outside of the constraints of elected officials to assess public interests and support for different plan structures. During the RTP development, the Business Coalition conducted confidential polls and other ongoing efforts to test the public sentiment toward particular plan options. During TPC deliberations, these members were able to present a realistic perspective on actions and plan attributes that would lead to success. For example, the business members of the TPC weighed heavily in the TPC’s official position on HB 2288 (the bill that would have authorized a new transportation district administered by the County Board of Supervisors). Although a majority of TPC members appeared not to support the bill, the TPC declined to vote to officially oppose HB 2288.15 This less confrontational approach promoted a better working relationship between the TPC and the state legislature.

During the drafting of HB 2292 (the bill that guided the development of the RTP), the Business Coalition, along with the TPC, offered consistent amendments to the originally proposed language. This united support resulted in the bill passing the legislature with only two no votes out of 114 total votes cast.16 The role of the Business Coalition and its ultimately successful campaign, Maricopa 2020, to extend the sales tax is also recognized in the acknowledgements in the RTP (below).

The business leaders of Maricopa County worked with government planners in a cooperative manner. They demonstrated a strong respect for the technical ability of the MAG staff, the planning process, and the criteria used to establish transportation needs. At the same time, they were resistant to delays in the process. They became advocates for the process and instigators of action.

The business community’s partnership with government planners is an enduring one. Beginning with the 1985 half-cent sales tax, the business community has participated in initiatives such as Vision 21 and Maricopa 2020. Currently the business community is leading a new effort, the TIME Coalition, to promote comprehensive statewide transportation planning.

Substantial, Dedicated Transit Funding

Relative to highway funding, public transportation receives less federal financial support in all urban areas of the United States. The 1985 sales tax measure dedicated only about 4 percent of funds to transit. In contrast, the MAG RTP provides one-third of the sales tax revenue to public transportation, including light rail.

The level and type of transit was one of the most contentious elements of the plan. While Phoenix focused on rail transit, the East Valley was more interested in bus service. The West Valley, just beginning its rapid development phase, needed new freeways constructed. The inclusion of transit in the plan also presented a significant hurdle in the state legislature. The more conservative legislators voiced concerns about the entrance of unions and subsidizing transportation options. In addition, one individual in the county launched a well-financed campaign against Proposition 400 (the 2004 referendum on the sales tax) largely because of the light rail funding.

In the end, the TPC reached some compromises on transit. Both bus and rail transit were crucial to the regional agreement on the RTP. The larger urban areas see these modes as an important means to fight increasing congestion. As one TPC member stated in the January 2003 meeting, “Phoenix voters have sent a clear message that they want to receive more than they did from the 1985 tax. At the very least we want to be able to say for our projects that 50 percent would go to freeways, and 50 percent would go to light rail/transit.” To appease some constituents, funding for operating costs for rail were removed the plan. At the same time, the TPC added a funding “firewall” to the plan that would prohibit any shifting of funds allotted for one mode to another mode.

The major investment in transit along with specific performance measures to evaluate success provides a strong basis for continued support of this mode. The varied and dispersed population of Maricopa County makes transit viable only in certain portions of the county; however, the continued promotion of a regional perspective will retain transit as a viable transportation alternative.

Regional Integration

The level of regional integration in the selection and funding of projects in the plan was a key component. The MAG region contains diverse jurisdictions at various levels of urban development. Each jurisdiction would ideally like to see its own needs met first. The RTP process managed to integrate different stakeholders’ concerns into a perspective that generally focused on the good of the region.

The TPC spent the first several months of their work considering how to address the tax referendum. Several funding splits were considered for the tax revenue. One option was to provide 50 percent of the tax revenue for regional needs and 50 percent to the local areas. This concept, called “return to sender,” was seriously considered but highly contended. The intent was for everyone in the region to gain with both the tax and the plan.

During these discussions, the TPC continued to return to the regional perspective as the best option for everyone. The West Valley provided direction to the TPC that “they support putting all the money into one pot to be used for those major projects that bring economic development and allow mobility by various means of transportation.” In the words of one TPC member, the jurisdictions decided to “grow up and act like a region.”

Conclusion

The passage of Proposition 400 in the November 2004 election validated the RTP decision-making process as well as the plan itself. The TPC’s year-long development process produced a plan that was truly regionally integrated and balanced both geographically and modally. The establishment of firm policy guidelines and performance measures, as well as fiscal and management auditing procedures, ensured that the plan will deliver what it promises.

Though much credit is due to MAG for the successful development of the RTP, the agency’s allies in the business community and in state government also played an important role. Business leaders helped MAG navigate an unusually complex string of legislative hurdles to authorize the development and funding of the plan. At the same time, the eventual buy-in of the state legislature, the governor, and the voters of Maricopa County created a plan with broad political support. The successes and innovations of the MAG RTP are already informing the development of other regional and statewide transportation planning efforts in Arizona.

Appendix A: TPC Timeline17

Transportation Policy Committee Progress

Appendix B: RTP Goals, Objectives, Performance measures, and evaluation criteria

SYSTEM PERFORMANCE MEASURES

Goal 1: System Preservation and Safety

Transportation infrastructure that is properly maintained and safe, preserving past investments for the future.

Objective 1A: Provide for the continuing preservation and maintenance needs of transportation facilities and services in the region, eliminating maintenance backlogs.

Performance Measure:

- Percentage of maintenance and preservation needs funded.

Objective 1B: Provide a safe and secure environment for the traveling public, addressing roadway hazards, pedestrian and bicycle safety, and transit security.

Performance Measure:

- Accident rate per million miles of passenger travel.

Goal 2: Access and Mobility

Transportation systems and services that provide accessibility, mobility and modal choices for residents, businesses and the economic development of the region.

Objective 2A: Maintain an acceptable and reliable level of service on transportation and mobility systems serving the region, taking into account performance by mode and facility type.

Performance Measures:

- Travel time between selected origins and destinations.

- Peak period delay by facility type and geographic location.

- Peak hour speed by facility type and geographic location.

- Number of major intersections at level of service “E” or worse.

- Miles of freeways with level of service “E” or worse during peak period.

Objective 2B: Provide residents of the region with access to jobs, shopping, educational, cultural, and recreational opportunities and provide employers with reasonable access to the workforce in the region.

Performance Measure:

- Percentage of persons within 30 minutes travel time of employment by mode.

Objective 2C: Maintain a reasonable and reliable travel time for moving freight into, through and within the region, as well as provide high-quality access between intercity freight transportation corridors and freight terminal locations, including intermodal facilities for air, rail and truck cargo.

Performance Measure:

- Average daily truck delay.

Objective 2D: Provide the people of the region with transportation modal options necessary to carry out their essential daily activities and support equitable access to the region’s opportunities.

Performance Measures:

- Jobs and housing within one-quarter mile distance of transit service.

- Percentage of major arterial streets that have bike lanes.

- Percentage of regional connectors funded as part of the total Off-Street System Plan and the Regional Bicycle Plan.

Objective 2E: Address the needs of the elderly and other population groups that may have special transportation needs, such as non-drivers or those with disabilities.

Performance Measure:

- Percentage of workforce that can reach their workplace by transit within one hour with no more than one transfer.

Goal 3: Sustaining the Environment

Transportation improvements that help sustain our environment and quality of life.

Objective 3A: Identify and encourage implementation of mitigation measures that will reduce noise, visual and traffic impacts of transportation projects on existing neighborhoods.

Performance Measures:

- Per Capita Vehicle Miles of Travel (VMT) by facility type and mode.

- Total transit ridership.

Objective 3B: Encourage programs and land use planning that advance efficient trip-making patterns in the region.

Performance Measures:

- Households within one-quarter mile of transit.

- Transit share of travel (by transit sub-mode).

Objective 3C: Make transportation decisions that are compatible with air quality conformity and water quality standards, the sustainable preservation of key regional ecosystems and desired lifestyles.

Performance Measures:

- Households within five miles of park-and-ride lots or major transit centers.

- Amount of pollutant emissions by type-National Air Quality Standards (NAQS).

PLAN EVALUATION CRITERIA

Goal 4: Accountability and Planning

Transportation decisions that result in effective and efficient use of public resources and strong public support.

Objective 4A: Make transportation investment decisions that use public resources effectively and efficiently, using performance-based planning.

Evaluation Criterion:

- Adopt performance measures that will result in a regional transportation system that is effective and efficient and meets the transportation goals and objectives of the region.

Objective 4B: Establish revenue sources and mechanisms that provide consistent funding for regional transportation and mobility needs.

Evaluation Criterion:

- Percentage of state and federal transportation taxes collected in Maricopa County that are returned to the region.

Objective 4C: Develop a regionally balanced plan that provides geographic equity in the distribution of investments.

Evaluation Criterion:

-

Geographic distribution of transportation investments.

Objective 4D: Recognize previously authorized corridors that are currently in the adopted MAG Long-Range Transportation Plan; i.e., Loop 303 and the South Mountain Corridor.

Evaluation Criterion:

- Inclusion of committed corridors.

Objective 4E: Achieve broad public support for needed investments in transportation infrastructure and resources for continuing operations of transportation and mobility services.

Evaluation Criterion:

- Voter approval for a regional transportation revenue source.

Endnotes

1 Arizona Department of Transportation, Historical Overview of the Regional Freeway System, September 2004. unpublished. p. 42.

2 Governor Jane Dee Hull, Executive Order 2000-16, http://www.azdot.gov/ADOT_and/Vision21/execorder.asp

3 Vision 21 Task Force, Final Report, December 2001.

4 TPC Meeting Minutes, September 21, 2002.

5 Regional Transportation Plan, November 2003, Chapter 1, p. 1-1.

6 TPC Responsibilities, MAG Regional Council.

7 Arizona Department of Transportation, Historical Overview of the Regional Freeway System, September 2004. unpublished. p. 35.

8 RTP, pp.1-3, 1-4.

9 TPC Meeting Minutes, September 21, 2002.

10 Ibid, Chapter 4, p. 4-1.

11 TPC Meeting Minutes, April 16, 2003.

12 TPC Meeting Minutes, June 18, 2003.

13 Regional Transportation Plan, Chapter 6, p. 3.

15 Ibid.

16 TPC Meeting Minutes, April 16, 2003.

17 MAG Website, http://www.mag.maricopa.gov/detail.cms?item=3362