US Department of Transportation

FHWA PlanWorks: Better Planning, Better Projects

| Framework Application |

|---|

San Antonio Texas Kelly Parkway

Ensuring Community Involvement and Environmental Justice

in a Highway Capacity Project for Urban Socioeconomic Development

Executive Summary

The Kelly Parkway project was a corridor study that looked at constructing an approximately 8.8-mile limited access highway in south San Antonio, Texas. With the closing of the Kelly Air Force Base, political and business leaders in the city viewed the project as a redevelopment opportunity for the base property and for the south San Antonio community. The highway would consist of two through lanes in each direction on a parkway-style road, connecting businesses, air, and rail facilities in south San Antonio to other major highways. The project area was 95 percent Hispanic and had a high rate of poverty, with 34 percent of reported incomes below the poverty level. By adapting pre-existing roads and constructing some completely new alignment, the Kelly Parkway would provide needed highway access to local residents, relieve truck congestion, and bring economic opportunities to the south side of the city.

The Kelly Parkway project is a good example of integrated transportation planning and the use of proactive community involvement. The distinctive innovations of the project were largely related to aggressive public involvement that reduced the likelihood of environmental justice claims by attaining active community participation and project buy-in. That same sense of active collaboration and participation was also applied to the project development process, which was a corridor-level NEPA study that brought together planning, design, and impact assessments.

The project offers many lessons and insights about urban highway development and the relationship to economic redevelopment initiatives. Participants attribute the success of the planning process to the following:

- A knowledgeable consultant who understood the Hispanic community

- A flexible team that worked well together and with the public

- Adequate funding for public outreach

- An integrated planning, NEPA, and design process

The local residents harbored a distrust of the former Air Force base and concerns over soil and water contaminants. Area residents were initially opposed to any “government” action, but Kelly Parkway was able to differentiate itself from other problems and distinguish itself as a transportation solution and a positive community development. As a result of proactive interaction, these concerns were converted into dynamic public participation. The roadway promised improved mobility and economic opportunity, which the area greatly needed. The project catalyzed the community, convincing them of the benefits of the improved roadway and involving them actively in developing project criteria and screening design alternatives. Project members encouraged these processes with their flexible and positive attitudes while ensuring that the needs of the community for better highway access, improved safety, and economic opportunities were addressed. The project became “a model” for how to seriously engage local communities, plan urban highways, and overcome considerable opposition and environmental justice claims.

The transportation needs of the community, however, were only one part of the Kelly Parkway initiative. The larger goals for redevelopment included the expansion of Port San Antonio as a hub of air, rail, and truck transportation, attracting businesses to the area, and the creation of jobs. Many of these elements have not moved forward as anticipated, and now Union Pacific Railroad is moving its freight hub out of the city. The Kelly Parkway project is currently on hold while funding and development issues are examined.

Background

In 1996, the City of San Antonio established the Greater Kelly Development Corporation (GKDC) in response to the impending closure of Kelly Air Force Base. The GKDC was an independent, nonprofit, redevelopment authority whose purpose was to oversee the redevelopment of the Air Force base into an industrial park named KellyUSA. GKDC’s main objective was to create or maintain 21,000 good-paying jobs at KellyUSA by 2006. Kelly Parkway was a concept that GKDC intended, in part, to support economic development in south San Antonio by providing efficient mobility and safe access into and around the KellyUSA businesses.1

The project was a limited corridor study to examine how to create a highway transit route from south San Antonio to State Highway 16. This urban road project studied how to adapt existing roadways, potentially utilize some Union Pacific (UP) railroad easement, and build a significant amount of completely new highway extending south out of the city. The area of south San Antonio is 94.4 percent Hispanic, and the central challenge to planners was a combination of extreme community skepticism, environmental justice issues, public involvement, and community stakeholder trust.

Driven by idealized political and economic goals, the community created a roadway plan to benefit the city as a whole, in terms of mobility, neighborhoods, and economic development. The corridor-based NEPA process produced an environmental impact statement (EIS) and a record of decision (ROD) that had strong community support. This was a surprising success in that the project team first had to gain the trust of a recalcitrant community and then show them how an infrastructure project could meet their many needs.

Project Overview

The Kelly Parkway was intended to provide efficient truck access to and from an “inland port.” The road would bring two through lanes in each direction from an urban shipping hub in the city south to open highway and farmland along State Highway 16. The proximity of UP railroad corridors and large runways meant the route could provide vehicle connections to a diversity of trans-shipment services in south San Antonio with easy and quick access out of the city to other major highways. At the same time, the redevelopment could add jobs and services to an underserved community.

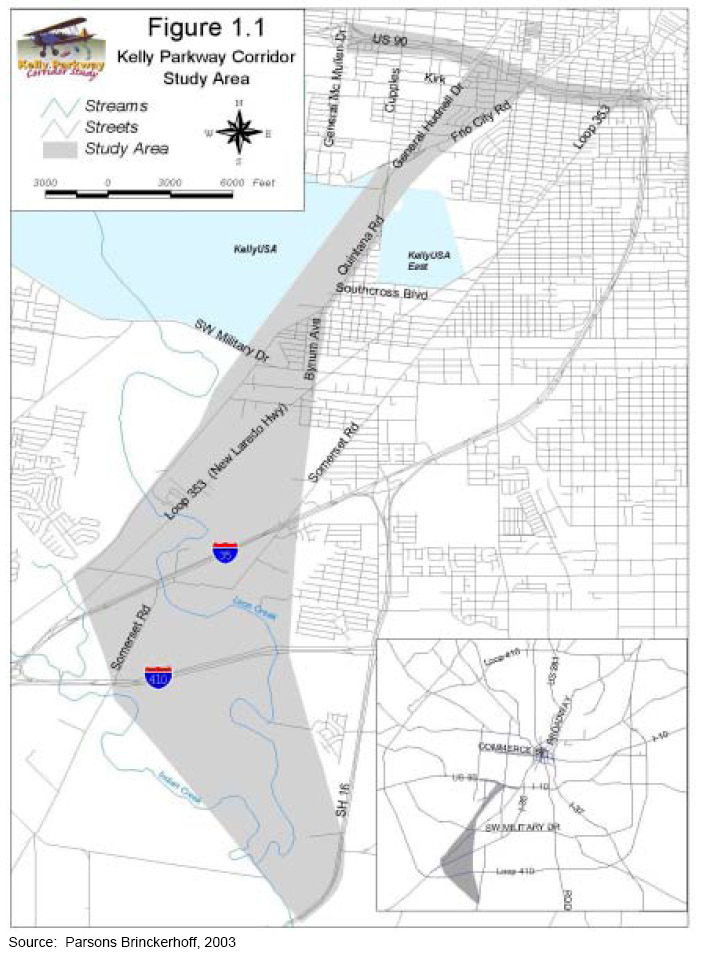

Figure 1. The Kelly Parkway Corridor Study Area

Union Pacific maintained a facility in the vicinity of Kelly Air Force Base called the Intermodal Terminal. The railroad brought in bulk goods to be transferred to trucks for distribution. The 11,500 foot runway designed for heavy duty Air Force cargo planes provided an unusual opportunity for air freight services. Although the Air Force was closing its operations at Kelly, city politicians and business leaders wanted to keep existing commercial services and businesses from relocating elsewhere and attract new ones. As part of the base closure process a redevelopment group, the GKDC, was established to evaluate how the city could best take advantage of the opportunities afforded by the base closure. Businesses related to the air industry were interested in the base facilities. As space became available, companies like Pratt & Whitney, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin moved into the former base facilities. To strengthen its plan to retain and add businesses to the area, the GKDC recommended a new highway to improve ground access.

The area around the former Air Force base had traffic problems well before the idea of KellyUSA as a business and industrial park emerged. The former base had been divided into two parts – the main Kelly post and Kelly East – that covered an extensive acreage. Several arterial and neighborhood roads, as well as the UP railroad, converged at a narrow passage between the two tracts of the base, called Kelly Crossroads. There, trucks crowded the existing routes such as Quintana Road and General Hudnell Drive. Nearby residents had to use these same routes or drive around the base. Furthermore, General Hudnell Drive had been designed specifically for periodic access to the base. It provided bulk traffic access from US 90 into the Air Force facilities, but there was no access to it from surrounding neighborhoods, creating fragmentation. It was clear that “it was not designed with any consideration for the community.” The communities were not happy with the configuration of the roads, truck congestion, or their safety in this arrangement. They were also distrustful of the Air Force and the government in general.

The community of south San Antonio is predominantly a Hispanic community of limited socioeconomic means. The redevelopment of the base facilities was intended to be an economic opportunity for the area that would provide jobs and improve services. The proposed Kelly Parkway would have been an urban arterial roadway that improved mobility, provided access to KellyUSA and neighborhoods, and connected nearby high speed transportation facilities. The community was not receptive to major government initiatives though. It had a history of being at odds with the Air Force base for various reasons, including hazardous waste contamination. When word spread that a business development group planned to build a highway to Kelly, it appeared to the community as just another way for the government to take advantage of it and disregard its concerns.

In 1997, the Southwest San Antonio Mobility Study suggested the need for traffic improvements through the Kelly Crossroads. The GKDC grasped this as a boost to their political and business interests. The San Antonio Bexar-County Metropolitan Planning Organization (SABC-MPO) included the project in the 2025 Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP), along with a Kelly Parkway Corridor Study. The city put the Kelly Parkway into its transportation plans, and the concept went to TxDOT to execute: “It was a difficult project in general…the base was essentially designed to keep people out, now they were redesigning to bring people in.”

Project Drivers

“Kelly Parkway was politically driven...the BRAC [base realignment and closure] decision to decommission Kelly AFB was very unpopular in this area…and the Kelly Parkway…was envisioned to support the redevelopment of the base into something productive for the community.”

The project was driven by the political and economic interests of redevelopment, and supported with a combination of traffic issues. Congestion along existing roads was common, and the arterial capacity was inadequate to support the local traffic mixture of people, goods and services in southwest San Antonio. The Union Pacific Intermodal Terminal generates a heavy level of traffic in the south San Antonio region. A long-term increase in truck traffic to and from the terminal was anticipated, as well as to the KellyUSA warehouse and industrial facilities. Two previous studies identified the need for improved transportation: The Southwest San Antonio Mobility Study (1997), also referred to as “the Mobility Study,” and the (similarly named) Mobility 2025 - Metropolitan Transportation Plan, released in December 1999 by the SABC-MPO. The Kelly Parkway Corridor study area included four freeways, which represent critical components of San Antonio’s highway network, and six major arterial roads.2 Level of service (LOS) ratings were calculated for projected 2015 average daily traffic (ADT) volumes on these routes. Without the Kelly Parkway each rating was an F.3 In 2000, the five major roadway traffic counts in the study area were as follows:4

- US 90 (Frio City Road to Nogalitos Street): 136,890

- I-35 (Loop 353 to Somerset Road): 36,830

- I-410 (SH 16 to Somerset Road): 36,690

- Quintana Road (Southcross Boulevard to Cupples Road): 20,880

- Loop 353 (I-35 to SW Military Drive): 4,670

As part of a larger redevelopment effort, Kelly Parkway was driven, in large part, by political and business interests. A presidential order gave five years to close the base, which finally took place in 2002. The GKDC needed the Kelly Parkway in order to optimize their plans for expanding KellyUSA. As a business hub, KellyUSA was poised to capture a portion of the increase in international shipping between Mexico, the US, and Canada promised by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Improved routes of access to KellyUSA were expected to generate economic redevelopment by expanding the air maintenance industry and rail freight services, attracting other services and businesses, and generally alleviating traffic in the nearby neighborhoods. The Parkway project was supported by then State Senator Frank Madla Jr., largely for the economic goals of redevelopment. “Senator Madla was really behind furthering the recommendations that came out of the Mobility Study, and pushed for the Parkway to be further developed.”

Secondary to facilitating economic development, Kelly Parkway would help address transportation needs and neighborhood safety concerns of area residents. The road would reduce traffic volumes through neighborhood streets by providing an alternative for truck travel and through traffic. This alone would reduce the risk of vehicle-pedestrian accidents. The Parkway would also have provided logical access points for local traffic and thus enhance mobility overall.

Initial Concept and Planning

The Southwest San Antonio Mobility Study suggested the need for Kelly Parkway in 1997. It proposed a linkage from I-410 to the Kelly Crossroads, an improvement of existing facilities north of Kelly Crossroads to US 90, and an extension south to SH 16.5 In 1999, the SABC-MPO incorporated two related projects into Mobility 2025, which first gave weight to Kelly Parkway as a crucial metropolitan transportation strategy in the San Antonio area. These related projects were widening the road between Kelly Crossroads and US 90, General Hudnell Drive, to six lanes and adding an interchange at US 90, estimated at $50.6 million. These aspects of planning fed into the development of the Kelly Parkway corridor-based NEPA study.

In both plans, Kelly Crossroads was the focal point. For years, Kelly Crossroads was the slot between the two parts of the Air Force installation; as a result, it has been an important point of convergence for San Antonio transportation routes. Any traffic moving between KellyUSA and KellyUSA East must pass through Kelly Crossroads. Five arterials and two railroad corridors pass through the junction. The parallel railroad corridors limit the potential for improvements on the west and to the south of the Kelly Crossroads area. The 1997 Mobility Study projected a 33 percent increase in truck traffic and concluded that a six-lane facility, like the Kelly Parkway, was necessary to accommodate the projected traffic.6 The roadway would allow direct access to UP’s intermodal rail terminal and KellyUSA, and the added capacity would allow more efficient movement of goods and people throughout southwest San Antonio with minimal disruption to surrounding neighborhoods.

In 2000, TxDOT conducted a Major Investment Study (MIS) and concluded there was reason to fund a corridor-based NEPA evaluation of the project. The Notice of Intent was published in June 2000 and the evaluation was started thereafter. The initial focus was on Kelly Crossroads, but was expanded upon a congressional request to take the project south to State Highway 16 to further increase connectivity. Planning and development began in 2000, and initial screening concluded that a parkway-type facility extending from US 90 on the north end to SH 16 on the south end and consisting of two through lanes in each direction was the preferred alternative. The parkway’s total length would be approximately 8.8 miles with full interchanges located at US 90, Kelly Crossroads, W Southcross Boulevard, SW Military Drive, Loop 353, I-35, and I-410, with a partial interchange constructed at SH 16. It would provide a route for employment and commercial traffic and improve access to and between major arterials for commuters. The Final EIS was completed in 2004 and the ROD signed in February 2005.

Major Project Issues

The major issues with the development of Kelly Parkway involved the local community, which had a considerably higher minority and low income population than the rest of the city, at 95 percent minority and 34 percent below poverty level. Issues of environmental justice were at the forefront of the project,7 and language and education levels were major barriers to sharing information.

The community’s skepticism of any major project stemmed largely from past actions by the Air Force and community concern about how its issues would be absorbed and addressed. The project team had no control over the base, or prevailing public sentiment, but those opinions became part of the dialogue for planning and developing the parkway.

Local residents’ concerns were linked to quality of life issues as well as safety. Contamination from the brownfields of Kelly Air Force Base was the biggest worry. “We set up for 100 people for the first [public] meeting, and 350 showed up, many carrying picket signs saying ‘Kelly kills’ in skeleton suits.” The community’s contention was that the Air Force had contaminated the groundwater in the past with solvents and new construction would cause further exposures. In addition, a newspaper article had reported an unusually high incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease) among the Kelly base workers.8 These health-related issues combined to make the local community generally distrustful of any large new “government” project.

Another major project issue was concern over traffic safety. Increased truck traffic was considered a major issue. If a new road was to be built, residents wanted to ensure pedestrian safety. Perhaps most of all, local residents wanted reassurance that the proposed parkway was in the best interest of the community and would not simply serve KellyUSA.9

The project development team anticipated these community issues and engaged local neighborhoods and community groups from the start. The team established a special office for community relations in the project area, developed a formal public involvement plan and hired a special sub-consultant specializing in Hispanic community relations. In its conversations with the community, the team focused on educating the community about the project’s benefits as well as planned mitigation efforts. Those efforts were the major part of the environmental impact analysis. Once the project team obtained community trust, the substantive elements of roadway design and other concerns emerged. Residents wanted grade-separated crossings to maintain access and increase safety. Businesses and community facilities would be displaced by construction, as well as many residences – disruptions that needed to be compensated. These were the issues of a typical urban highway project, and they could be dealt with as part of the process.

Institutional Framework for Decision Making

The GKDC initiated the parkway concept, coming out of the base closure process. The base facility became KellyUSA, and the GKDC became the managing and operating authority charged with facilitating development of KellyUSA into a major business and industrial park. The panel was composed of former military officers, business leaders, and city councilmembers. The group was subsequently renamed the Greater Kelly Development Authority (GKDA). The facility was later renamed the logistics center Port San Antonio, presumably to better reflect its purpose, and the management corporation was renamed the Port Authority of San Antonio. The GKDC formed a Kelly Transportation Task Force made up of the MPO, TxDOT, the City of San Antonio, and Bexar County.

The two transportation plans of 1997 and 1999 (The Mobility Study and Mobility 2025) had both identified the Kelly Parkway project, or elements of it, for planning. TxDOT’s internal mechanism for authorizing transportation project development is the Unified Transportation Program. Priority One projects of the program are approved for construction within the next three years, and Priority Two projects are those in the process of preliminary development/design, or environmental clearance, and are slated for construction approval in Year 4 through Year 10 of the program.

In the late 1990s, TxDOT also conducted Major Investment Studies for projects, aimed at setting parameters and goals. A pre-Major Investment Study Transportation Stakeholders meeting in July 1999 included representatives of TxDOT, FHWA, SABC-MPO, VIA Metropolitan Transit, City of San Antonio, and Bexar County. The group decided that roadway improvements to accommodate bus transit and trucks would best address the needs in the Kelly Parkway Corridor, and that no transportation systems management (TSM), mass transit, or high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) alternatives should be included in the alternatives screening process for this project.

The project went into the NEPA study with highway transportation as the preferred objective. FHWA shared the lead with TxDOT, which retained the services of Parsons Brinckerhoff (PB) as lead consultant. The Air Force Base Conversion Agency was a cooperating agency on the EIS. Other agency involvement in the NEPA process was typical and not extensively collaborative. However, TxDOT enacted many agreements with agencies to expedite the environmental review process, including the 1998 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between TxDOT and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) on wildlife and threatened and endangered species, and the corresponding Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) on habitat descriptions and impacts; a Programmatic Agreement (PA) among FHWA, Texas Historical Commission (THC), Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), and TxDOT on historic properties; and an MOU between TxDOT and THC on local historic properties.

There was not a newly created level of agency cooperation for the project or an environmental management system; however, community involvement efforts had a spillover effect with various agencies. According to the project team, “We had adequate funding. We could dedicate a lot of people to get things done. We were able to get agencies to sit down together, which is usually a hurdle.” The public involvement specialists involved federal agencies early on in a series of update meetings. “This approach gave us early signals of what concerns were, so we could get the EIS out with minimal problems.” The project team met every two to three months with federal, state, and local agencies (without the public).

Much of the agency involvement was conducted from a negotiated standpoint of MOU and MOA. The 1998 TxDOT and TPWD MOU provides a formal mechanism by which TPWD may review TxDOT projects that have the potential to affect natural resources. The MOU was developed to assist TxDOT in making environmentally sound decisions and to develop a system by which information TxDOT developed may be exchanged with TPWD to their mutual benefit. Procedures and methodologies for providing habitat descriptions and impact descriptions are explained in an MOA. “The EIS committee should have had some of these agencies involved… but they wouldn’t be. We did have a special meeting with Corps of Engineers regarding wetlands. The impacts were minor and handled routinely, all done in-house…”

An unusual participant in the Kelly Parkway project was Union Pacific. The proposed corridor for Kelly Parkway ran adjacent to the UP rail lines, and UP owned a lot of the land adjacent to the parkway corridor. The parkway development team met with the railroad early on, and a UP representative served on the TWG committee; however, the railroad did not have the same legislative reasoning for getting involved in the process, as did the resource agencies. The railroad’s concerns with Kelly Parkway were twofold: 1) how the two forms of transportation would link together, and 2) public safety. The Kelly Parkway team planned to link to the UP intermodal facility. According to the UP, “Our ROW would be impacted, but it could be an asset.” The railroad did not want to give up land, but saw the benefits of better highway access to their freight operations. There was also the issue of safety. “These projects, especially roads, need to plan with the railroad up front.” The idea was that advanced planning could avoid grade crossings and other “retrofits,” and help the road and rail work together optimally and safely. At one point, between the August 27, 2002 public meeting and the release of the Draft EIS (DEIS), Union Pacific Railroad made a commitment to sell the tracks that parallel General Hudnell Drive.

An extensive Public Involvement Program (PIP) was initiated at the beginning of the project. It began with scoping and offered the public a variety of opportunities to participate in the process. The PIP incorporated three major components, including:

- Information gathering

- Community involvement

- Public information and education

Interwoven into these three components were four underlying principles, to:

- Build on existing community partnerships and communication networks;

- Develop, distribute and display high quality, innovative, user-friendly and community appropriate information;

- Coordinate closely with local jurisdictions, community organizations, and neighborhood organizations; and

- Respond in a timely manner to questions and concerns raised throughout the EIS process.

Engaging the community was foreseen as the major issue for the project. A proactive team of planners and facilitators prepared for substantial community involvement. Linda Ximenes of Ximenes & Associates, Inc. acted as the liaison between the Kelly Parkway Corridor Study team and the local community within and around the study area. Ximenes specializes in public relations and organizational development and is experienced in designing and conducting innovative activities to increase community participation in the study process. The project manager proposed opening a public involvement office, which opened in the northern end of the study area to facilitate the exchange of information with the public. Additionally, the project established four advisory committees:

- The Community Issues Committee (CIC), which was composed primarily of neighborhood representatives, property owners, small business owners, farmers, school districts, chambers of commerce, and other special interest groups, including opponents to the project;

- The Kelly Parkway Advisory Committee (KPAC), which was composed primarily of elected officials and public agency directors;

- The Technical Work Group (TWG), which was composed primarily of engineers, planners and environmental specialists from TxDOT, FHWA, FTA, the City of San Antonio, Bexar County, MPO, VIA, Air Force Base Conversion Agency, Department of Defense, and Union Pacific Railroad; and

- The Aesthetics Issues Committee (AIC), which was composed of citizens, landscape architects, and planners.

These committees were active in the project development process. They met at critical points in the process such as project milestones, to provide input and guide project activities and deliverables. They participated in developing the alternatives, setting up the screening criteria, and assisting the project team in going through the screening process. Over time, as participants became more versed in the issues and processes, the project team was able to present the committees with options and the members helped “make decisions based on the logic and constraints facing the project.” Complete lists of committee members and their affiliations can be found appended to the end of this case study. The Public Involvement Plan is listed in the references section under Rivera and Wooten (2003).

Transportation Decision-making Process / Key Decisions

The early decision processes were largely political, with economic development in mind. The highway concept originated from the redevelopment initiatives of the GKDC and the transition from an Air Force base to a commercial park. It is unclear how much the GKDC accomplished towards the parkway. The organization was a “quasi-public entity, affiliated with the city, with a taxing authority,” and has undergone major reorganization and change in staff. The group itself had issues. The City of San Antonio Ethics Advisory Opinion (No. 34 of October 4, 1999) issued by the City Attorney’s Office determined that City Council members could serve as members of the GKDC. However, the Texas Attorney General Opinion (JC-225 issued May 22, 2000) reached a contrary conclusion. The GKDC changed to the GKDA, and the facility from KellyUSA to Port San Antonio. Regardless of the corporation, the redevelopment of the former base became a city priority and the need for a new roadway to service the facilities and the south part of the city took on a momentum of its own.

The majority of the information on the planning and development of the Kelly Parkway comes from the NEPA process, which was also the planning process in this case: “It was a NEPA process and corridor study – all in one – and encompassed NEPA, public involvement and corridor studies and concluded with the ROD and geometric schematic.” Perhaps the most key decision was made by TxDOT in choosing the consultant, Linda Ximenes of Ximenes & Associates, Inc. for the project. TxDOT anticipated the community dynamics. When it interviewed the short list of consultants, it asked questions in Spanish. The consultant had to have the engineering expertise, but TxDOT selected the project team it felt was best suited to do public involvement within a Hispanic community. That decision had a considerable effect on the project outcome.

Road Type

As a corridor study, the first major decision was to determine the type of road. The team compared a range of roadway types and evaluated them against the project’s purpose and need to identify the best types for further analysis. The criteria for roadway selection included: community and environment; economic development; cost dffectiveness; operational performance; and design, mobility, and community/corridor integration.

The roadway/facility type was decided at a Preliminary Design Conference (PDC) held in April 2000, at TxDOT. Project members had to define the roadway types, in order to make an informed selection. In the process, Roadway Type 3 (Parkway) was chosen. This roadway type has two through lanes in each direction, for a total of four lanes, with grade separated interchanges at major intersecting roadways with on and off ramps. No commercial development or driveway access is provided along this type of facility. There would be an additional lane or auxiliary lane in each direction, which would provide access to some minor local cross streets, which would be dropped through the interchanges. On and off ramps would be provided at major intersecting roadways, and intersections with local roads would have a right turn in/right turn out, T-intersection for local access. The design speed of the roadway would be between 50 and 60 mph, and there would be landscaping between the through lanes as well as to separate the roadway from the local street system.10

Once a parkway was selected as the roadway type for further evaluation, a tri-level screening process was used to determine reasonable alternative alignment concepts. The first level of screening narrowed the entire range of potential options, which were developed through public and stakeholder involvement, to the most viable “Top 40.” The “Top 40” alternatives were determined to be routes that had even a remote possibility of meeting the purpose and need of the project and were in line with the goals and objectives of the study. Specifically, the key factors informing this decision were:

1. Purpose and needs statement

2. Project goals and objectives

3. Input from the working committees, stakeholders, and general public

4. Sensitive issues/area within the study area

5. Environmental and operational constraints

Public Involvement Efforts and Issues of Community Concern

Getting the community on board was the most challenging aspect of the project. The public involvement went through several phases that included educating the community about the highway planning process, garnering the community’s input and trust, and then getting them engaged in the substantive elements of the roadway design. The first stage was defining the project in the eyes of the community and addressing lingering community concerns.

The public involvement was a collaborative effort between experienced team members at PB, the prime contract firm, and Ximenes & Associates, the public relations sub-contractor. The project established a storefront public involvement office that became the base of public outreach activities. The facility was located in a shopping center with ample parking. It was handicap accessible and was located near a major transfer station operated by VIA, the public transit system in San Antonio. This was a high transit and pedestrian location within the project area, and thus within the community. It was big enough to hold most meetings, accommodating up to 100 people. Project team members facilitated staffing of the office, which was open two days a week. The office became a recognizable focal point for the project within the community, providing the means for direct contact with the project team, and disseminating project information to the community. As the project developed, design plans were kept there for anyone to come and see. The office also kept copies of project newsletters and other information.

The project staff spent considerable time explaining that Kelly Parkway was not an Air Force project, as well as differentiating their work from the development corporation. Much of the public involvement effort focused on this distinction. Many officials handling the redevelopment at the GKDC were former military officers and the community had been previously upset with the Air Force’s operations at the base and its handling of hazardous waste.

Hazardous waste comprised the big environmental issue of the project. The project team addressed this in several different forms. The community had filed suit against the Department of Defense (DOD) for allegedly allowing solvents from engine repair to enter the water system. The development of the parkway was underway at the same time the base closure process was conducting remediation of contaminants on the base property as part of the closure procedures. For better or worse, the local community viewed both processes as one and the same. The Kelly Parkway development team had a goal of minimizing impacts and was also concerned with the proper disposal of contaminated soils. To the community, however, it was viewed as an extension of Kelly Air Force Base, and thus as part of the problem. The community involvement team, through its committees, devoted considerable time convincing the local public that their project was indeed in the best interest of the community and they would strive to minimize the impacts of hazardous materials, such as contaminated soils and groundwater.

Another major element of the hazardous materials issue was less defined – it stemmed from a generalized fear of the potential unknown health effects. The community felt that it had a high level of health impacts because of the base. In response, the Air Force gathered statistics on the community and found that cancer rates were below normal. Nevertheless, the local community believed something was wrong. Soon after, a newspaper article claimed that incidents of Lou Gehrig’s disease among base workers were excessive. This was first published around October 2000,11 and the data to discount it were not available until November 2002. All the while, Kelly Parkway was in development.

In addition to the Air Force, there was the development corporation. The project area was in the poor southwest part of San Antonio. According to one interviewee, the GKDC “thought jobs would be white collar jobs for… those in the North part of the city.” While that may have been a goal of the GKDC, the Kelly Parkway team had to break down that perception and convince the community that the roadway had benefits to south San Antonio. Those education efforts were not simple. They had to be presented in Spanish to a population of whom many were immigrants. Additionally, the options could not be presented, “so that you needed a Ph.D. to understand them.”

Moreover, the community was not passive. Local activists formed CEJA – Committee for Environmental Justice Action. The goal of CEJA was to obstruct anything to do with Kelly Air Force Base. They had studies that showed contamination sat on top of the water table and CEJA felt the Air Force was in denial about dumping solvents into the local drainage system. CEJA picketed the first public meeting and was clearly the most organized voice of community opposition.

The project development team faced general suspicion among the community in addition to organized resistance, but its major breakthrough also came from a long-standing community organization – Communities Organized for Public Service (COPS). Founded in 1974, COPS is an organization of 26 parishes in the predominantly Hispanic area of south San Antonio. It is a powerful grass roots organization with a lot of clout in San Antonio due to its active participation in local government affairs and because of its affiliation with the Catholic Church and ability to organize.12 The project team identified a priest affiliated with COPS who they thought could help the project. They explained to him their goals and set about convincing him of the project’s benefits. As soon as the priest said he was behind the project, community relations improved. He started talking with community members to help them see the positive benefits of Kelly Parkway, such as economic development, increased connectivity, and opportunities for beautification of the community. According to the Kelly Parkway project manager, the priest was a key project champion. As a highly-respected authority figure within the local Hispanic community, his opinions had considerable weight. Though his involvement was informal and project members were unclear exactly what he did to help the process, his influence was cited multiple times in interviews as a turning point in public involvement efforts.

The project team conducted over 100 stakeholder meetings throughout the course of the project, and participation ranged from meetings with individuals to large groups of over 100 stakeholders. Meetings with agencies, community contacts, as well as additional research, identified primary stakeholders, which included representatives from neighborhood groups, the Air Force, businesses, special interest groups, churches, public agencies, and political jurisdictions. Coordination with local and public agencies ensured open communication and validated that project activities were in line with other planning efforts in the area. Staff briefings were important in keeping elected officials, involved agencies, and constituents knowledgeable of developments in the planning process.13 Three major public meetings were held on July 11, 2000; February 20, 2001; and November 7, 2001. The team conducted “special issue workshops” where the public could learn about and discuss specific elements related to environmental and social impacts, and the process of managing them. Some topics of the special issue workshops included:

- Understanding the TxDOT Project Development Process

- Understand the TxDOT Right of Way Acquisition Process

- What is an EIS?

- How Are the Alternatives Screened?

- Truck Traffic and the Transport of Hazardous Materials

- Bicycle and Pedestrian Path Accommodations

- Truckers’ Workshop for Freight Carriers

In addition to the public involvement office, the team maintained a website (ADA accessible and also provided in Spanish) to ensure information was readily available to the public. The website included public information on the study, a list of upcoming opportunities for public involvement and an opportunity for the public to submit comments via e-mail. The project team further provided the public and stakeholders with periodic project updates through the Kelly Parkway Newsletter. Seven editions were sent to 3,000 people in the stakeholder database.

Screening Decisions and Goals

In the mechanics of public involvement, most issues were dealt with through the project committees. At the beginning of the project there was a lot of opposition. All decisions had to be completely transparent. As one project member said, “We brought [the committees] into the process and they would do the work.” The committees interacted with the public, soliciting comments on the range of options. The goal was to do public workshops, but some of the initial meetings were so crowded they had to have one person talking at a time. The process shifted to a lot of meetings with small working groups, which would then report out. The project team held about 50 small or individual meetings to work out alternatives and five or six large public meetings: “A lot of the smaller meetings were ‘we go to them’ meetings. We gave presentations, gave them updates on the status and got their input.” Among the project members there were “differences in opinion about how much should be structured and how much should be organic in the decision-making process.” Some aspects of the design and planning had to be decided by the project team and presented to the public, but other times the community needed to work out the solutions for themselves. The consultant project manager was an engineer and often wanted to present materials to the public, but his public relations specialists preferred involving the public in the process. “It was a tension, but a healthy tension… it worked well. It was a good balancing act by the [project] team on how to approach things, and we used either strategy at different times.”

The Kelly Parkway Corridor Study formalized a screening process for examining alternatives and making decisions.14 The “Top 40” was the first major round of alternatives. The “Top 40” was then re-evaluated to a much narrower “Six Pack,” which actually consisted of eight alternatives, a semi-alternative and a no-build alternative. The screening of these alternatives was conducted against the same criteria as the initial roadway type analysis. More specifically, within the project development process, previously identified project goals and objectives were used to screen and evaluate the remaining alternatives, which were identified in the FEIS as follows:

- Mobility Goal: Provide an efficient multi-modal transportation network that provides accessibility to, from, and between the KellyUSA redevelopment sites;

- Community and Environmental Goal: Identify and address the potential social, economic and environmental impacts and benefits;

- Operational Performance and Design Goal: Provide a future transportation facility that considers operational performance and complies with current TxDOT and nationally recognized transportation standards;

- Cost Effectiveness Goal: Provide a future transportation facility that effectively balances costs and benefits;

- Economic Development Goal: Respond to planned land uses of the KellyUSA redevelopment sites as well as those within the study area; and

- Community/Corridor Integration Goal: Integrate the future transportation facility with community needs and land uses within the corridor, with particular consideration to aesthetic and landscaping aspects.

The analysis was conducted over a series of screening meetings with stakeholders, including the Community Issues Committee (CIC) and Technical Work Group (TWG), with the purpose of eliminating the least viable alternatives, as opposed to determining the “best” alternatives. The “Six Pack” of alternatives was then carried forward for further analysis in the EIS.15

Within the EIS, a screening matrix summarizes very detailed areas of impacts of 10 alternatives (the eight derived from the “six pack” process plus one modified, as well as the no-build alternative) in relation to the usual range of environmental impacts. Impacts included land use, farmland, social environment, relocation, economic, pedestrian and bicycle access, air quality, noise, water quality, waters of the US, floodplain, ecosystem, historical and archaeological resources, Section 4(f), hazardous materials, visual and aesthetic resources, and energy. Additionally, construction impacts, irreversible and irretrievable commitments, and secondary and cumulative effects were examined.16 PB conducted the research, with subcontractors for several parts, including cultural resources and hazardous materials, and the public involvement discussed earlier.

The screening process used a qualitative matrix concept, looking at greater and lesser effects. The six levels –good, better, best, bad, worse, worst – were all given numbers so they could evaluate each criterion of each alternative by adding them together.

Ultimately, one alternative (Alternative 5) emerged as both the "community preferred" and the "environmentally preferred" alternative. As a result, this alternative became the “recommended alternative.”

Hazardous Materials and the Environment

The hazardous materials issue took other forms beyond the base contamination issues. The community wanted the design of the new roadway to have adequate secondary containment for trucks. Corrigan Consulting, Inc. had the job of analyzing hazardous materials. KellyUSA was being designed as a shipping depot. Even when the community understood that the parkway planners would minimize impacts during construction, they wanted secondary containment along the new road in case of a truck accident or toxic spill. According to one interviewee, “We met with all the emergency responders, found out response times for hazmat spills, working with TxDOT’s hazmat people – meting with them – taking everyone’s advice and bringing results to each meeting for the CIC [Citizen’s Issues Committee].”

Ultimately, there were very few issues related to natural resources. The consultant team thought they would have wetlands issues. Leon Creek was a major creek that went through the corridor, although it turned out to have already been disturbed. Since it had previously been mined for gravel, it did not end up creating any issues for Kelly Parkway. Aquifer draw down rates almost became a problem late in the process. The project area sits atop the Edwards Aquifer, an artesian water source and the home of unique natural communities. The USFWS looked at potential development along the corridor and expressed concerns that the aquifer and the wildlife that depend on it couldn’t handle the anticipated rate of draw down. The northern portions of the roadway were urban, but extending the parkway south to US 16 meant the southern portion traversed farmlands. Farmers had wells to tap into the aquifer for irrigation purposes. USFWS was concerned that the southern stretch of Kelly Parkway would induce sprawl, but as a member of the project team said, “we’d limit access on the roadway and that shouldn’t prompt too much development.” The area contains active farmland, which would limit development opportunities. Other programs in the San Antonio area are actively seeking alternative water supply sources for the city’s growing population.17

The project team anticipated environmental justice as a main issue from the start. The team’s active efforts to engage the community minimized the effect environmental justice might otherwise have had. It was apparent the project would have had disproportionate effects on the minority Hispanic population in the area. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, federal agencies are required to ensure that no person, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin, is excluded from participation in, denied the benefits of, or subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal funding.18 Moreover, Executive Order 12898 directs each federal agency to achieve environmental justice. Ensuring these goals meant getting the community actively involved in the project planning and development. Thus, the greatest challenge was gaining the community’s trust of the project team.

Aside from environmental justice, the community’s concerns were similar to those for any roadway project. According to the project team, “We heard from the community: we don’t want another grey ribbon of cement through this neighborhood.” The Aesthetics Issues Committee (AIC) wanted the roadway to look nice like the northern parts of the city. The goal of the aesthetics committee was to resolve the desires of the community for appearances, while attending to the technical elements of the environment and roadway design. They also wanted the project to provide optimal community mobility. “As a local, I was interested in improving access for the community. [In the case of General Hudnell Drive,] you can see the road, but can’t figure out how to get there if you are driving around in the community.”

Once the community was actively engaged in selecting project criteria, environmental justice was reduced to procedure. Ten categories of land use data were studied, which were extracted from the City of San Antonio’s Master Plan Policies of 1997. Additional plans were consulted, including the city’s Community Building and Neighborhood Planning program, the Southside Initiative Community Plan of 2003, the Master Plan for Lackland AFB (used to understand accident potential zones), the Largest Employers Directory - 2000 Edition compiled by the Greater San Antonio Chamber of Commerce, population and demographic data from the US Census, and information on neighborhoods from the City of San Antonio Planning Department’s Neighborhood and Community Association Database. The socioeconomic information “was pulled basically from trend-based data taken from [these] other studies.” The idea was to facilitate improvements over the city’s previous examples. The team “went in and said we know you were ignored last time as a low-income community. We want your input and for you to be part of the process. That had a lot to do with the success. They came up with a slogan that we were going to ‘do it better than the North side.’”

In terms of air quality, the San Antonio region was “near non-attainment.” The status of near non-attainment means an area is very close to falling into non-compliance with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards. The San Antonio/Austin area has been designated by the TCEQ Office of Policy and Regulatory Development as near non-attainment for planning reasons. As a result, the project team had to carefully examine the potential impacts of the project using air quality data provided by the MPO. Additionally, TCEQ worked closely with the project team to assure that air quality would not be significantly impacted by the project.

The project design was carried to approximately 30 percent during the corridor-based NEPA study. “There was a lot of push at the time to get a lot done on the project. It did end up being fairly detailed.” That said some of the trickiest issues were left to be dealt with later, especially purchasing the right-of-way. “Design elements for mitigation would come in the next phase. We don’t always have mitigation plans completely developed when we are still in schematics.”

The team finished the EIS in 2004. It made mitigation recommendations for various resources, listed the permits necessary, and explored the issues of acquiring the right-of-way. The NEPA decisions were not necessarily endorsed for permitting purposes. Any Section 404 permit application will require wetland delineation and a mitigation plan.19 It is unclear whether the project would meet TCEQ classifications for a Tier I (small project), or if it would be considered a Tier II and consequently it may require further review for a Section 401 water quality certification.

The Texas Division Office of FHWA signed the Record of Decision (ROD) for Kelly Parkway in February 2005. The proposed Kelly Parkway, from US 90 to SH 16, has an estimated cost of $400 million. The 8.8-mile long facility will be a limited access four-lane facility constructed by TxDOT.20

Current Status

Despite the initial interest of the SABC-MPO in the project’s development, the organization has not mustered funding for construction of the project. The yearly TIPs of 2004-2006 do not list the project. A portion of it, the Kelly Crossroads reconstruction, is listed in the 2008-2011 STIP as a project with environmental clearance, but no funding is allocated for activities. Interviewees say the right-of-way purchase would constitute the next major step and will require substantial funding and another difficult phase of public involvement, neither of which is currently feasible. Options for minimizing or sharing the cost of property purchases and relocations are being examined. In the meantime, city planners can use the EIS to protect the corridor from conflicting development. The SABC-MPO’s long range plan, Metropolitan 2030, lists the Kelly Parkway as a tolled roadway with a planned fiscal year of 2035. No funding is allocated, and the project is designated as an unspecified public-private development agreement.

In November 2006, Union Pacific announced it would build a new $90 million intermodal terminal facility 13 miles south of downtown San Antonio. The new 300-acre San Antonio Intermodal Terminal (SAIT) will open in early 2009 with truck and auto access to Route 35. Advanced computer systems will coordinate the movements of railcars, trucks, trailers and containers at the facility, greatly expediting the transfer from one mode of transportation to another. The project constitutes a major move by UP from city to suburb, and a major modification in the traffic demands and projected need for Kelly Parkway. When it opens, the new rail facility will draw much of the truck traffic out of the south San Antonio urban community.

Lessons Learned

Success Factors

The Kelly Parkway project is a good example of integrated transportation planning and the use of proactive community involvement. Distinctive innovations of the project are largely related to the public involvement process, which aimed at reducing the possibility of environmental justice claims by attaining active community involvement and buy-in for the project. That same sense of active collaboration and participation was also applied to the project development process, through the corridor-based NEPA study which incorporated planning and design.

Public Involvement and Community Impacts

Environmental justice was the primary issue anticipated in the Kelly Parkway development. All highways have community impacts. The goal in this case was to minimize those impacts to the maximum extent possible by working closely with the local community and design a roadway that had real community benefits. Engaging the local community in planning and designing a highway development project is the ultimate application of context sensitive solutions. In the case of Kelly Parkway, the community’s Hispanic heritage, socioeconomic status, and Spanish language were hurdles the project had to work through. Success was due to the project team’s experience, as well as the level of funding to engage and work through potential issues to find a collaborative solution.

The level and quality of the public involvement was directly related to the funding. “The level of opportunity for interaction afforded by the budget was really unique. Typically a big budget is for ads – mass outreach – not outreach at a more personal level.” In this case the funding was for community outreach, and the project team could use it as they saw fit. Most interviewees pointed to the importance of the public involvement office; they noted that there is “not usually funding to do that.”

There was a personal aspect to the community involvement as well. In the case of Kelly Parkway, the use of context sensitive solutions meant knowing the community and being able to effectively engage them and bring them into the process. TxDOT picked their consultant strategically and developed a good team with a combination of local people who had insight into the community, as well as those who brought expertise on process and insights from elsewhere. These details and personal characteristics paid off in project efficiency. Members of the project team rode bikes through the neighborhoods and met with people one on one. It worked so well that they have been invited across the country to talk about the public involvement process and how it was made into a success against such odds. One project member said, “We went and did career days at the local middle school, and picked up trash through the neighborhoods on the weekends. We would go and eat breakfast with people – pulling people into committee meetings. A dozen of us had a two-and-a-half to four year commitment on the project.” Another project team member remarked, “Knowing that it would be hard going into it, it did work out well. [Our TxDOT PM] called it a textbook example. We got minimal comments because we covered everything early in the process.” Yet another said, “The project was made almost impervious to community opposition.”

The environmental justice issues of Kelly Parkway project were dealt with efficiently. On a separate track, the process raised the visibility of the community and their issues at a national level. In 2003 the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice, in collaboration with the Federal Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice, awarded a grant to Project ReGeneration: Building Partnerships for Livability and Sustainability in the Greater Kelly Area, San Antonio. The grant was part of the Environmental Justice Revitalization Projects and separate from the Parkway development. It is focused on identifying ways to ensure constructive dialogue and building effective partnerships between community-based organizations, relevant federal, state, and local agencies, and other stakeholders.21

Integrated NEPA Process

In addition to active public involvement, the project process integrated all planning, design, engineering, and NEPA. As one interviewee said, “Planning and NEPA were totally integrated… That was the success factor of the process. NEPA is a planning process, so you can’t really separate out the parts. It should be integrated into one process.”

The intense public involvement had a collaborative effect that spilled over into other areas of the planning process. “TxDOT wanted the Feds involved so they would ‘live in’ the project, be a part of the decision-making process, not just receive a huge EIS in the mail and try to make a decision. They wanted everything to be as smooth as possible when it got to the decision points.” This same philosophy of transparent decision making was also used with the public, through the committees. Active involvement leads to robust decisions that have broad agreement.

Some decisions were made in relation to other planning documents. “TxDOT has lots of MOUs and such with cooperating [resource] agenciesthey’ve been going on for years. It does make it easier… until they renege, or decide they don’t like how you’re doing it.”

Additionally, simple agreements were put in place regarding permitting during the NEPA process, since agencies were involved throughout. Since the project has not moved forward, it is not known if these informal agreements will hold up over time, particularly since the actors involved may have changed, but it is expected that “things should follow through.”

Avoiding Re-Opening Decisions

Interviewees about Kelly Parkway noted, “Minor agreements affected the process.” The project had a massive public involvement effort and wanted to avoid any backsliding in the process. That meant that meetings had to effectively recap decisions already made and point clearly to what was needed to keep a forward momentum on track. This included other principles of project management, such as “don’t let sleeping dogs lie.” When something looked as if it might become an issue, they engaged it early to deal with it, finding it best to “meet early and meet often. Look for opportunities. It doesn’t have to be adversarial.”

Flexibility

“A flexible process was the key to the success,” explained one stakeholder. The challenges of the public involvement could have derailed the efforts of Kelly Parkway development or caused significant delays and costs, but the project team kept a flexible attitude and learned from each step how to better complete the next. That flexibility applied to the interactions of the agencies and groups as well. “[The consultant] didn’t have to rewrite a subcontract to have archeologists look into something [that] goes to the flexibility of TxDOT to get things done.”

Key Innovations

Public Involvement Office

Establishing a storefront public involvement office was a simple step in the planning process, but its positive effects were visible and widespread. The choice of where it was established was context sensitive, helping the office be as effective as possible. Stakeholders explained that “the public involvement office was on a bus route, and right near where people went to pay their bills. It served as a place for meetings and a repository for project information. It ended up being very valuable.” “[The consulting] firms and TxDOT are usually off in big offices, not within the community.”

Multiple Roles for Planners and Project MembersWillingness to Step Outside the Box

Interviews with Kelly Parkway project members indicate they had to play many roles outside of ‘traditional’ transportation planners. Many of their actions were similar to anthropologists, educators, or politicians. Attending church services and presenting information at school career days got the community’s attention and helped build the stakeholder trust the project needed. To engage a reluctant community in the planning process the Parkway project members had to reach out to them, and to do so at tactical locations within the community.

The willingness of the project team to interact with the community was also a major factor in the success of the planning. Some people like to go to an internet site and read information, but in the south San Antonio community many people wanted to sit down and discuss the project with someone they trusted. Community members stated that “the door-to-door and going to their meetings were definitely the most successful approach” and “the key element of success was that there was a lot of two-way communication, where there was back and forth and response.” When the public outreach sub-consultant was asked to identify the most important factors in gaining public support she cited the rental of the storefront office, the door-to-door approach of the project team, and the funding that enabled those activities.

The public involvement specialists stressed that outreach should take a multi-level approach: “some things will touch some people and some things will touch others.” Delivering project information in many formats was the strategy for reaching a wide audience, “but the personal stuff is always the best. Because we had so many meetings, people knew us.”

Tracking and Recording the Planning Process

The project’s leaders carefully tracked their progress to evaluate what worked and where the team stood. As one team member said, “Minor agreements affected the process. For that reason, we kept an administrative record along the way. We had someone specifically dedicated to that and it probably took 50 percent of their time -- keeping track of communications. If you average that out over four years, that’s like 4,000 hours. If you tried to put that into your project budget it would never fly, but it was so important to this project.” With the issue of environmental justice hanging over the project, and a community that had already filed suit against the Air Force, careful documentation of the process and proceedings was a necessary safeguard. However, the carefully documented process also served as a record of progress and decisions made and helped keep momentum moving forward.

Barriers Encountered and Solutions

Overcoming the Air Force Base

Kelly Parkway reacted in relation to base activities. The community disliked the base and feared serious health risks from it. They also had a tendency to view all major development projects as derived from the government and designed to take advantage of, or at least discount the concerns of, minority and low-income populations. The project team had to win them over in many innovative ways.

“The biggest challenge was to separate military issues from transportation issues,” despite officers’ role in the redevelopment agency which commissioned the Parkway. The Kelly Parkway project had to engage the community, and thus had to engage the legacy of Kelly Air Force Base and the history of community distrust. The roadway offered a solution to many deficiencies of the south San Antonio area, but the project team had to make this clear. Community buy-in on the Kelly Parkway would only be achieved by differentiating the issues of the base closure from the development of the roadway.

Project leaders said, “We encountered folks still mad at DOD and the city--they would come to meetings and picket to arouse suspicions about the project because the government was involved.” The community of south San Antonio was ultimately won over to the project, but the public involvement process had to understand the community to get at the basis of its concerns. Other projects that anticipate significant environmental justice issues or community resentments need to understand the sources of community opposition in order to work around it.

“A lot of what we did was calming people down about concerns, especially about their homes. Some residents said please, please buy me out! While others said: over their dead body. There was a whole range of opinions.” The health concerns, a major focus at the start, fell by the wayside as the project progressed; some were unfounded, and it was apparent that the Kelly Parkway project was not a cause.

Complexity of Planning Process

The intensive public involvement of the Kelly Parkway project highlighted the fact that highway planning is a complex and alien process to most people. The project needed community involvement, but that required a steep learning curve about agencies, environmental issues, roadway engineering, funding options, and more. The success of Kelly Parkway required extensive education, much of which was focused on the process itself. “The planning process is difficult for people to understand. It takes a lot of education to remind people where you are in the process…They didn’t get that the decisions narrowed options along the way.”

The Role of Key Individuals

The Parkway project has lessons that can be applied to other projects, but many elements of the Project benefited specifically from the efforts of key individuals. Those values are more difficult to quantify or to extrapolate to other situations. Not every highway project gets an experienced team, individual qualities are sometimes not apparent, and it is difficult to anticipate how individual qualities will affect the process. In the planning stages of the Kelly Parkway, State Senator Frank Madla was able to galvanize support for the development of KellyUSA and pushed the city and TxDOT for a transportation solution to aid the redevelopment goals. In the NEPA process, the Project Manager was a natural fit. He had the right skills to direct the process and was also able to personally engage the issue of community involvement, meeting with community members and discussing the project in Spanish. The Catholic priest was clearly an opinion maker, and the public involvement activities of the Parkway benefited from his support.

Agency Participation

In the case of Kelly Parkway, agency collaboration and interaction was not critical. The Kelly Parkway was primarily about environmental justice or minimizing it through active community involvement. This element of the project work was spearheaded by the consultants. “We tried to bring in other agencies, but we couldn’t really get anyone to be cooperating agencies--it requires a monetary commitment. We might have gotten one at the very end--but across the board, when we invited them to scoping meetings, to take part in things, they never show up. It isn’t in their funding for them to have staff to participate. So, we get their comments at the end.”

Formal agreements between agencies such as MOUs or Programmatic Agreements facilitated routine review of resources and impacts. These types of agreements, however, can also serve to keep agencies at arm’s length from each other. Collaboration and early involvement on a project are beneficial, but can go against entrenched and long-standing procedures, and present a challenge to the planning process. For example, “new guidelines had just come into place that said we should integrate the 106 process into the NEPA process. So we set up a meeting with the SHPO,” but it fell through. “It’s still never been done in Texas, and we thought to be the first one would be a fiasco.”

Several interviewees commented on the lack of continuity among agency staff. Highway projects can take many years to plan and the 2000 to 2004 timeframe of the Kelly Parkway planning process was relatively short compared to some projects. Still, in that time the project had at least four FHWA representatives. If the project finally goes to construction, FHWA and TxDOT will need to refine the designs and look at mitigation. Resource agencies will need to re-examine the environmental considerations at that time and see if they still hold up.

ROW Purchase and Relocations

A difficult hurdle for the Kelly Parkway project - purchasing the ROW and relocating residents - has yet to begin. This phase of the project will require more public interaction and involvement. Data found that 54 percent of residents in the project area have no mortgage, which probably indicates a high proportion of renters. Nevertheless, ROW acquisition will be very expensive, and the funding is not available. Although the EIS is complete, there are no plans to move forward with the project. One interviewee pointed out that “the EIS can be used for making local planning decisions.” After years of planning and work, most of the project participants have taken similarly optimistic perspectives. The reality is that design has not been taken forward any further, the project is waiting for funding, and the traffic demands are in flux.

Railroads

Nearly all interviewees for the Kelly Parkway project commented on the mysterious nature of the railroad. Railroads were in the San Antonio area first and have substantial land claims. DOTs have legal authority to acquire most private properties, but not from the railroads. Railroads pass directly through urban cities, and they own considerable amounts of prime property across the US. The railroads have learned to guard their holdings and use them strategically. Union Pacific was willing to work with the Kelly Parkway planners because the project was mutually beneficial. Port San Antonio hopes to capture some of the container shipping that is currently going through Long Beach, California, and provide a relay between the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico. Union Pacific is the largest freight carrier through Laredo from Mexico, “but most of that freight runs through San Antonio; it’s not dispersed there.”

TxDOT felt that, “UP made strides with Kelly Parkway in trying to work with us without revealing too much of their hand to the competition. But anytime the railroad is involved it is difficult.” Railroad personnel interviewed for this case study felt they had a good working relationship with the Kelly Parkway project, but cited the difficulties of working with the development corporation (now Port Authority). The community group CEJA protested the announcement of the new rail port, mainly on the grounds of air and noise pollution.

Funding

The biggest barrier to the Kelly Parkway now is funding. The cost is estimated at around $400 million. Senator Madla had helped the project in its early stages. “He pushed the need along, but not the funding.” The “elected officials” meetings (as the KPAC committee was known) were devoted to looking at a lot at creative funding methods. “I never understood why TxDOT put such a level of effort into the project. It became a model [of public involvement], but I don’t know that they’ll do it again. They seemed very intentional about it. I think it may have had to do with the State Senator… [But] even when he was around, it was pretty clear the funding wasn’t coming through.”

Texas has encouraged regional authorities to find local funding mechanisms for needed highway projects, and in 2003 Bexar County leaders created the Alamo Regional Mobility Authority (ARMA) to develop a tollway system for the San Antonio area.22 “Six years ago they were looking at tolling projects1604 and 281 could become toll roads, and it was thought that the excess funding would support the Kelly Parkway.” Toll conversion is very controversial, and the San Antonio toll system is still being examined.23 There have been some political earmarks for the Kelly Parkway project, but not nearly enough to proceed.

“There was political excitement early on but it never had funding. It’s still not therea little money to do a few things, but not a lot.”

Changing Initiatives and Needs

This case study points out the volatile nature of road projects driven by political and economic initiatives. The Kelly Parkway started as one project in 1997 and ended as another in 2004. It was initially meant to serve the transportation needs of a commercial industrial park and shipping hub. The Port Authority (formerly GKDC) saw the Parkway as a necessity for their development. When the project got close to completion of the EIS, however, the Port Authority wanted special things included in Kelly Parkway that just couldn’t be done. Then they stopped being involved. No direct interviews with Port Authority personnel were conducted for this case study. The staff has changed since the Parkway development, and speculation on their motivations are based on the comments of other interviewees. “They decided [the Parkway] was no longer a priority to them. They need to develop road networks within their own property lines.”

The goals for redevelopment in the area have shifted over time as well. The development of San Antonio as an inland port and center for trade processing activities has gone in unpredicted directions. “Port San Antonio had a joint use agreement with the Air Force to use the runway for commercial uses, but after 9-11 they lost some of that opportunity, and the operations of the port were changed.” Moreover, the railroad had problems with the Port Authority. “[The Port Authority] was always trying to adapt things to their benefit… They wanted bridges over the railroad with the road extending into East Kelly.” “The Port Authority wants [Kelly] to be a hub, but it isn’t.” Now the railroad has decided to move their freight yard south, out of the city, which holds implications for changing the demand of Kelly Parkway to meet intermodal freight needs.

As intensive efforts at community involvement ramped up the goals of the Port Authority were modified. The roadway planning process is now remembered as one that met the community’s goals, but the traffic needs and economic redevelopment initiatives remain unclear. It is possible that the Port Authority has decided to focus less on intermodal capabilities and more on business development within the complex. The south San Antonio community was counting on the socioeconomic development the Parkway would bring, and that was part of the equation for obtaining their cooperation. What’s more, the freight trucks might go away. That would alleviate some congestion but the community still needs better highway access through the Kelly Crossroads and onto other major arterials such as General Hudnell Drive. “The project would be hugely helpful to the community, but it’s expensive, and it’s just not warranted traffic-wise.” “With UP moving their facilities, it will make traffic demand numbers even lower.”

Conclusions

The Mobility 2030 plan lists the Kelly Parkway, from US 90 to SH 16 as a toll roadway on partial new alignment.24 The estimated cost is $400 million, and has a private sector comprehensive development agreement. No funding is approved and some form of public-private partnership, probably in collaboration with the Port San Antonio, will be necessary to get the Parkway built. UP has changed the traffic equation by moving their facility out of town, but that could open up new ROW in the south San Antonio area. The next step for the Kelly Parkway will depend on whether or not the funding falls into place, whether the necessary roadway still resembles the one that was originally planned and if the Kelly Parkway EIS can hold upover time and over changing needsas an adequate environmental review.

References:

ARMA

2007 The Alamo Regional Mobility Authority. Website available at: http://www.alamorma.org/

Environmental Insider News

2003 Environmental Justice in San Antonio. May 2003.

FHWA

2004 Kelly Parkway, from US 90 to SH 16, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas, Final Environmental Impact Statement. Report prepared by FHWA and TxDOT, in cooperation with the Air Force Base Conversion Agency. http://kelly-parkway.com/ADAcompliant/index_a.htm

Purcell, Brian

2005 San Antonio Freeway System; Tollway System. Texas Highway Man website. http://home.att.net/~texhwyman/tollsys.htm

Rivera, Rudolofo “Rudy” J. and Raquelle Wooten

2003 Public Involvement Plan for the Kelly Parkway Corridor Study Context Sensitive Design. Paper presented at the second Urban Street Symposium, Anaheim, California, June 2003. http://www.urbanstreet.info/2nd_sym_proceedings/Volume%202/Rivera.pdf

San Antonio ExpressNews

2000 Connection or Coincidence? ALS disease is plaguing workers from Kelly, Oct 20, 2000, Page 1A.

SABC-MPO

2005 Mobility 2030 San Antonio--Bexar County Metropolitan Transportation Plan.

2008-2011 Transportation Improvement Plan http://www.sametroplan.org/pages/Programs_Plans/TIP/FY08_11/FY%202008-2011%20TIP%20Final%20Document.pdf

Technology Talks