US Department of Transportation

FHWA PlanWorks: Better Planning, Better Projects

| Framework Applications |

|---|

FHWA Leads the Planning Process for Redesign of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge

Executive Summary

Since 1961, the Woodrow Wilson Bridge has carried traffic over the Potomac River between Maryland and Virginia. It is part of the I-95 system, the main north-south route on the east coast. Initially designed to carry 75,000 vehicles per day, the bridge experienced traffic volumes of 195,000 vehicles per day by 2004. Consequently, heavy traffic congestion and major delays became daily occurrences on the bridge, leading to regional demands for a new and larger bridge. Excessive traffic loading also took a toll on the bridge, accelerating its deterioration and raising valid safety concerns.

Because the federal government owned this aging bridge, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) petitioned Congress for funds to replace it, with both Maryland and Virginia being major players in this effort as well. FHWA led the planning for the bridge replacement, starting in 1989, and completed a final environmental impact statement (EIS) in 1997. The adequacy of that statement was quickly challenged in court, but ongoing project redesigns also cast doubt on the sufficiency of the EIS to support pending federal permitting decisions.

When the project was enjoined by the District Court for the District of Columbia, FHWA had to decide whether to appeal, comply with the Court’s order, or take a combination approach. This decision was complicated by the fact that the existing final EIS had already had its draft EIS supplemented twice. Nevertheless, FHWA decided to prepare new supplemental draft and final EISs while also appealing the District Court’s decision.

While deciding to move forward with additional impact analyses, FHWA did not change its position on the basic issue that was being litigated: selection of a 12-lane bridge as the preferred alternative in the first EIS and dismissal of a 10-lane structure for detailed analysis on the basis that 10 lanes could not meet long term traffic capacity needs and, therefore, could not meet the purpose and need for the project. A federal district court agreed with opponents who requested that a 10-lane bridge be analyzed in the EIS as a reasonable alternative. FHWA appealed this decision. The Court of Appeals, in reversing the district court, agreed with FHWA’s position that only the alternatives that meet the project’s purpose and need must be analyzed in the EIS, and accepted as reasonable FHWA ‘s position that a 10-lane bridge did not meet the purpose and need. Not only did this court decision resolve a fundamental question on the design of the bridge, it set a significant national precedent in framing the scope of alternatives that need to be analyzed in an EIS.

In addition to the challenge of addressing this litigation, FHWA had to address difficult interagency and community coordination issues given the bridge’s location within two states and the District of Columbia. To address these issues, FHWA:

- Assembled an experienced team of mangers and consultants to address complex environmental impact questions on dredging, aquatic resources, and cultural resources;

- Re-opened direct and effective communications with numerous federal and state resource agencies; and

- Established collaborative decision-making teams that included local communities and citizens.

Through this collaborative approach, FHWA reached consensus on a high quality design for the bridge.

As FHWA identified potential adverse environmental impacts in the supplemental EIS process, the agency worked closely with the resource agencies to develop mitigation measures. In consultation with the cooperating agencies on the EIS, FHWA took a broad perspective in considering potential mitigation measures; that is, discussions and decisions were not limited to minimum protections but included efforts to improve affected resources in a more regional, ecosystem based approach. This perspective resulted in a very comprehensive package of mitigation measures. Excellent examples include the establishment of fish reefs in the Chesapeake Bay with thousands of tons of the old bridge and the installation of fish passageways on Rock Creek and Anacostia River tributaries.

To assist in the implementation of the mitigation and ease potential concerns, FHWA established an independent environmental monitor to observe and report on the completion status of all agreed upon mitigation. FHWA complemented this monitoring approach with development of a comprehensive database, tracking, and reporting system and made that system accessible to the regulatory agencies involved. The independent monitor and tracking system were successful from FHWA’s and the resource agencies’ perspectives and have been replicated on other large highway projects.

FHWA met its goal of completing concurrent NEPA and Section 404 permitting processes and used the draft and final supplemental EISs to serve as the initial and final permit applications, respectively. The US Army Corps of Engineers was a cooperating agency on the supplements, held joint public hearings with FHWA, and issued its Section 404 permit approximately two weeks after FHWA completed its final supplemental EIS and signed a record of decision (ROD).

Background

Project Overview

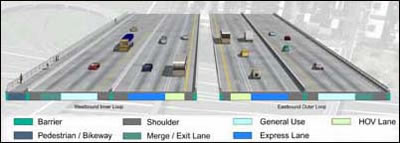

T he Woodrow Wilson Bridge project area is a 7.5-mile section that runs from west of Telegraph Road in Virginia to east of Indian Head Highway in Maryland along the I-95/495 Capital Beltway (Figure 1). The bridge component includes two new, side-by-side drawbridges with 12 lanes and 70 feet of vertical navigational clearance at the draw span. Ten of the 12 lanes are conventional highway lanes, and the two additional lanes are for alternative transportation options that may become feasible during the 75-year life expectancy of life of the bridge. These options may include trains, buses, high occupancy vehicles, express toll lane service, high occupancy toll lanes, or another special purpose.

he Woodrow Wilson Bridge project area is a 7.5-mile section that runs from west of Telegraph Road in Virginia to east of Indian Head Highway in Maryland along the I-95/495 Capital Beltway (Figure 1). The bridge component includes two new, side-by-side drawbridges with 12 lanes and 70 feet of vertical navigational clearance at the draw span. Ten of the 12 lanes are conventional highway lanes, and the two additional lanes are for alternative transportation options that may become feasible during the 75-year life expectancy of life of the bridge. These options may include trains, buses, high occupancy vehicles, express toll lane service, high occupancy toll lanes, or another special purpose.

The lane configuration separates local and long-distance travelers. Full shoulders are provided across the bridge. The new bridge also accommodates a pedestrian/bicycle path.

The design of this box-girder bridge features 32 fixed spans supported on V-shaped piers. These piers offer the look of arches but provide a more open appearance with smaller foundations than a true arched design. The new bridge is 20 feet higher than the original and will allow most boats to pass underneath. FHWA predicted that once the project is complete, the number of bridge openings will be reduced to about 65 a year, or less than two-thirds of the current number of yearly openings.

The project also includes the redesign and reconstruction of the Capital Beltway as it approaches the new bridge from both the Maryland and Virginia sides. Four new interchanges will allow travelers to more easily enter and leave the highway. The current estimate of the entire cost of this ongoing project is $2.5 billion, including a federal share of $1.6 billion.

Project Drivers

The Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge opened in 1961 as a six-lane structure designed to carry a volume of 75,000 vehicles per day (Figure 2). Constructed and owned by the federal government, the bridge carries the Capital Beltway over the Potomac River, connecting Alexandra, Virginia to Prince George’s County, Maryland. The Capital Beltway (I-495) is a part of I-95, the main north-south interstate route on the east coast of the United States. The bridge is also a drawbridge that opened approximately 200 times per year.

O ver the decades, traffic increased on the bridge as a result of both through-traffic and regional commuters. In September 2004, the daily traffic volume was 195,000 vehicles, far surpassing the designed capacity. This heavy traffic resulted in severe congestion, aggravated by an eight-lane beltway feeding into a six-lane bridge. The congestion contributed to a particularly high accident rate and expedited the bridge’s deterioration.

ver the decades, traffic increased on the bridge as a result of both through-traffic and regional commuters. In September 2004, the daily traffic volume was 195,000 vehicles, far surpassing the designed capacity. This heavy traffic resulted in severe congestion, aggravated by an eight-lane beltway feeding into a six-lane bridge. The congestion contributed to a particularly high accident rate and expedited the bridge’s deterioration.

Regional businesses and the commuting public frequently voiced their complaints to the political establishment inside the Capital Beltway, emphasizing frequent congestion on the bridge and resulting major delays as the most noticeable bridge problems. Because the bridge was federally owned, FHWA testified before Congress on several occasions in support of funding requests for planning and for construction. In making these requests, FHWA leadership assured Congress that lengthy planning and construction delays would be avoided and the project would stay on schedule.

Thus, the existing and growing problems of traffic congestion on the bridge, deteriorating structural conditions, safety, the region’s almost daily frustration with this congestion, and Congressional oversight were the major drivers for replacing the bridge.

Initial Concept and Planning

FHWA maintained the following four goals for the project:

- Provide adequate capacity for existing and future travel demand by improving operating conditions and fixing the bottleneck caused by eight Capital Beltway through-lanes converging into six lanes across the river;

- Facilitate intermodal travel, such as transit or High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes, bicycling, and maritime access up the Potomac River;

- Improve safety by reducing the number of accidents and improving access for emergency response vehicles; and

- Protect and improve the character and nature of the surrounding environment.

In 1989, FHWA, along with agencies in Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, began examining alternative approaches to solving the bridge’s capacity and structural problems. FHWA also studied the potential effects on the adjacent communities of rebuilding the bridge, including potential impacts to well known archeological and historic resources located on the Virginia side of the Potomac.

FHWA issued a draft EIS in August of 1991. This draft EIS analyzed five alternatives for replacing the bridge, each of which would expand the bridge to 12 lanes. Because this draft EIS met with significant public dissatisfaction, FHWA formed a twelve member Project Coordination Committee to assist in the identification of additional alternatives. The membership included senior level officials from FHWA, the Virginia, Maryland and District of Columbia transportation agencies, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the National Park Service, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the City of Alexandria, Virginia, Fairfax County, Virginia, Prince George’s County, Maryland as well as state-level elected leaders from the affected region. The Committee subsequently considered over 350 alternatives, and on a consensus basis recommended many of these for more thorough screening by the EIS development team.

FHWA also facilitated public involvement in the identification of alternatives by establishing panel groups and focus groups. To accommodate consideration of the alternatives, FHWA supplemented its 1991 draft EIS twice, releasing their first supplemental draft EIS in January 1996 and the second in July 1996.

Also in the mid-1990s, the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge Authority Act of 1995 granted consent to Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia to establish, by interstate agreement, the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge Authority, and authorized the transfer of ownership of the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge to that Authority. Maryland and Virginia eventually negotiated an agreement for joint ownership of the new bridge.

FHWA issued its final EIS, which included consideration of eight alternatives, in September 1997. FHWA included one “no build” alternative and seven build alternatives that all envisioned a 12-lane structure. The preferred alternative consisted of two parallel, six-lane drawbridges. In November 1997, FHWA selected this preferred alternative in its Record of Decision (ROD).

Approximately two months later, in January 1998 the City of Alexandria filed a lawsuit alleging that FHWA violated several requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act. Alexandria eventually reached a settlement with FHWA in March 1999 and before the first trial, but the lawsuit was continued by three Alexandria based organizations acting as plaintiffs.

In April 1999, the District Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs on all three allegations. Under NEPA, the court concluded that FHWA had not afforded detailed consideration to a 10-lane river crossing as a reasonable alternative and had only given cursory treatment to the potential impacts of the construction phase. The court found FHWA’s implementation of Section 106 to be defective, reasoning that the Agency could not adequately take into account the impacts to protected historic properties because it postponed identification of the sites that were to be used for construction-related purposes. Because compliance with Section 106 is an initial procedural step in completing the Section 4(f) requirement to minimize harm to historic properties, the court also concluded that FHWA failed to comply with Section 4(f). FHWA appealed the district court’s opinion to the DC Circuit Court, which reversed this lower court’s decision in December 1999. Plaintiffs then asked for a hearing before the Supreme Court, which denied that request.

In overruling the lower court, the DC Circuit Court did not agree with the district court’s position that a 10-lane bridge was a reasonable alternative. The district court had found it to be a reasonable alternative based on the smaller bridge’s ability to reduce much of the projected traffic congestion while having less of an adverse environmental impact than a larger bridge. However, the Circuit Court concluded that for an alternative to be reasonable, it must meet all of the objectives of the federal action. The Circuit Court further concluded that it was reasonable for FHWA to narrow the project’s objectives to resolving the transportation and safety issues being experienced by the bridge, and a 10-lane bridge was only a partial solution to them. On the less critical issues regarding the adequacy of the analysis of construction impacts, the Circuit Court found the analysis not to be as tersely presented as the district court had found. Postponing the identification of construction sites was also determined to be permissible for Section 106 and Section 4(f) compliance purposes because the sites were primarily construction staging areas that were ancillary to the to the project, not normally identified until the design stage of the project, and subject to a Section 106 Memorandum of Agreement with the appropriate cultural resource protection agencies.

While litigation was proceeding, FHWA continued to implement commitments from the 1997 ROD, including a bridge design competition. Four firms, who submitted a total of seven concepts, were declared finalists. A panel chaired by former Maryland Governor Harry Hughes announced the winning concept at a November 18, 1998 press conference.

This case study primarily addresses the remaining project development process that occurred after FHWA signed its November 1997 ROD.

Figure 1. Rendering of Designed Lane Distribution

Major Project Issues

In 1999, approximately 10 years after starting the planning process for replacing the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, FHWA and sponsoring agencies re-evaluated design changes to the preferred alternative identified in the 1997 final EIS. FHWA concluded, based on allegations in the unresolved litigation and a strong recommendation from the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), that a supplemental draft and final EIS were required to address the changes.

FHWA’s decision to prepare the supplement was not without controversy. The location of the project within the National Capital region and the need for a Congressional funding authorization had placed the project under a unique microscope. The additional time needed to prepare the supplement could delay the start of construction and add to its costs. Because FHWA had already prepared two draft supplements on the first EIS, the agency had to assure its detractors that the new supplemental draft and final EISs would be completed expeditiously and without any further setbacks.

As the sponsoring agencies and resource agencies re-assembled in early 1999 to begin another effort at completing a satisfactory EIS process for the bridge, FHWA knew that several major agencies were unhappy with the inter-agency consultations that had occurred to date, some potentially major construction impacts were unresolved, public concerns remained, and litigation over alternatives was ongoing. FHWA recognized that in order to meet its commitment to Congress that construction would begin in the fall of 2000, it had to quickly gain the full cooperation of a variety of affected agencies and organizations.

After the completion of the ROD for the first FEIS, FHWA determined that the bridge could not be built as envisioned in that EIS, creating a major complication to achieving agency and organization cooperation. Constructability reviews during the bridge design concept competition revealed that the construction concepts assumed in the 1997 FEIS would not work with the type and size of structure now being considered. Providing access for the heavy equipment that would now be necessary to handle the proposed large steel girders and foundation elements was projected to require a substantial increase in the amount of dredging and sediment removal with associated larger impacts to submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV). Other increased adverse impacts were projected for noise, wetland and woodland loss, and endangered species. The need for increased mitigation closely followed from the need to analyze these increased impacts. However, FHWA understood that the relatively confined nature of the project site limited the ability to identify mitigation onsite or near the project site.

Although FHWA had addressed new impacts and a number of years had transpired in the EIS process, FHWA still faced a basic dispute over the best alternative for crossing the Potomac. Some parties continued to recommend a tunnel crossing and a 10-lane bridge rather than FHWA’s preferred 12 lanes. This dispute was not only before the federal courts as the FHWA team commenced the supplemental draft EIS, but, more significantly, the District Court ordered FHWA to analyze a 10-lane bridge.

The 1997 FEIS had addressed a limited range of cultural resource impacts because it looked mainly at the bridge’s footprint. Consequently, identification and treatment of cultural resources was a major remaining issue in the development of a supplemental draft EIS because support areas for demolition, staging, and other activities would affect a much larger area than previously anticipated. With a rich history dating back to a tobacco port in the early 1700s and history as a noted center for many founding fathers, Alexandria, Virginia has a large historic district. The bridge was immediately adjacent to two Alexandria cemeteries: St. Mary’s Cemetery which is the oldest continuously operating Catholic cemetery in Virginia, and Freedmen’s Cemetery, where African Americans who were freed during the Civil War are buried. In addition, the banks of the Potomac in Maryland and Virginia contain numerous archaeological sites, historic homes, and monuments. Jones Point Park, located underneath the bridge on the Virginia side, contains numerous cultural resources, including a historic lighthouse, remnants of a World War I shipbuilding facility, and the southern cornerstone for the District of Columbia (although the land was ceded back to Virginia in 1848).

Institutional Framework for Decision Making

Involved Agencies

The replacement of the bridge involved a broad mix of authorities. Unlike more traditional intra-state highway projects where the affected state’s department of transportation has the lead role in completing the NEPA document, FHWA took the lead in preparing the supplement because it owned the old bridge and the bridge improvements, as opposed to the interchanges, which were state owned but 100 percent federally funded. Other federal agencies with major decision-making roles included the US Fish and Wildlife Service, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, National Park Service, US Coast Guard, US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

In addition to FHWA, the sponsoring agencies for the supplement included the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), the Maryland State Highway Administration (MSHA), and the District of Columbia Department of Public Works (DCDPW). USACE joined FHWA as a cooperating agency so that it could use the supplements as its NEPA compliance documents for its pending Clean Water Act permitting decisions.

All of the above agencies plus others comprised a 29-member Interagency Coordination Group (ICG). The local members included the City of Alexandria and Fairfax County in Virginia and Prince George’s County, Maryland. State-level members included the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Maryland Department of the Environment, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, and District of Columbia Health Department. The ICG continued to meet through the construction process and reviews the status of promised mitigation measures. The ICG meeting minutes are maintained and available at the two project offices in Virginia and Maryland.

Of the four sponsoring agencies, the District of Columbia was the least affected by the project. Approximately 700 feet of its land were affected plus it had responsibility for operating the draw span of the old bridge. The District’s primary jurisdictional interest was to relinquish this operational responsibility for the new bridge, which did. The District consequently limited its role to commenting on draft documents, and approved both the draft and final supplements.

Community Involvement

FHWA went well beyond traditional methods to inform and involve the public in the development of the supplemental EISs. In order to provide the public with easy access to project documents, it opened project offices in Alexandria, Virginia, and Oxon Hill, Maryland. Outreach methods and techniques included fact sheets, resource papers, newsletters, open houses at project offices, a speakers’ bureau, quarterly breakfast briefings for elected officials, a web page, and public visiting hours at its consultants’ project site office(s). For a project with such a small project study area, FHWA also went beyond normal practice when it held two public hearings on the supplemental draft EIS. One hearing was held in Alexandria at the request of Alexandria residents, and the other in Prince George’s County, Maryland, because the impact issues of concern varied substantially between these geographic locations.

Figure 2. Internal and External Coordination and Issue Resolution

In addition to using a variety of methods to inform and involve the affected region, FHWA and its cooperating agencies used these tools extensively. Community briefings and workshops were frequently and regularly scheduled and requests for speakers or special briefings quickly granted. FHWA recognized that in the project development process for the bridge an important goal was to keep the public informed and involved. It achieved this goal through comprehensive efforts and the use of public relations experts who crafted clear and consistent project information.

Collaborative Decision-making Elements

An important collaborative component occurred with respect to the design of the bridge. As part of the first EIS, FHWA had signed a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) in October 1997 that stipulated various steps that FHWA must take to avoid impacts to cultural resources. Because the design and size of the bridge could both physically and visually impact nearby significant historic properties, especially those at the foot of the bridge in Alexandria, a major stipulation of the MOA addressed the development of the bridge’s final design and established several design goals for the bridge:

- The bridge shall be a structure designed with high aesthetic values, deriving its form in relation to the monumental core of Washington, DC and shall be an asset to the Nation’s capital and the surrounding region;

- The concepts for the bridge shall be based on arches in the tradition of notable Potomac bridges, for example, Key Bridge and Memorial Bridge;

- The bridge design shall employ span lengths which minimize the number of piers occurring in the viewshed of the Alexandria Historic District;

- The bridge design should preserve or enhance views along the Potomac River toward the National Capital and the Alexandria Historic District and

- The project shall be designed to avoid all temporary and permanent impacts to the Freedmen’s Cemetery.

In order to ensure that these design goals were met, the MOA further stipulated that a Design Review Working Group be established prior to the initiation of the detailed design phase for the purpose of providing comments. The members of the Working Group were the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, National Park Service, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Maryland Historical Trust, the District Historic Preservation Office, Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, City of Alexandria, and Prince George’s County.

T he Working Group met for two days and reviewed the design concepts submitted by the four firms who were the finalists in the design competition. They were able to reach a consensus on a high quality design that included long spans and an arch design similar to other Potomac River bridges in the Capital area (Figure 5).

he Working Group met for two days and reviewed the design concepts submitted by the four firms who were the finalists in the design competition. They were able to reach a consensus on a high quality design that included long spans and an arch design similar to other Potomac River bridges in the Capital area (Figure 5).

A second major collaborative component was inserted into the project in late 1998 when FHWA formed stakeholder participation panels. FHWA proposed and organized four panels: Telegraph Road Interchange Panel, Jones Point Park Panel, Route 1/Washington Street/Urban Deck Panel, and MD Interchanges Panel. FHWA defined stakeholders as those individuals and groups directly affected by the project including bridge users. The stated purpose of the panels was to identify valued community characteristics, define community goals and guidelines for the final design, and work with designers and planners to co-develop concepts and proposed designs that enhance and preserve the natural environment, the built environment, and the social environment of the community. It was made clear to prospective panel members, however, that alternatives would not be revisited and that the preferred alternative was the focus of the panel’s work.

FHWA sought a balanced and representative group of panel members and utilized a nomination process with selections made by elected officials and other community leaders. Panel members came from local chambers of commerce, environmental interest groups, local governments, the American Automobile Association, and bicycle route proponents. All panel meetings were open to the public and recorded with meeting minutes.

Panel members met approximately once a month over the course of a year and worked with design consultants to reach a consensus on designs. Proposed designs that were 20-30 percent complete were made available for review at public information meetings in Virginia and Maryland. Based on public comments, the design consultants made additional refinements in consultation with panel members. Next, designs that were considered to be 60-70 percent complete were presented at a Virginia Design Public Hearing. Following additional refinements from the results of this public hearing, the Virginia panels’ recommendations were provided to the Virginia Technical Coordination Team (TCT) for its decisions. The Virginia Technical Coordination Team consisted of the VDOT Project Manager and Bridge Engineer, FHWA Project Manager, FHWA Virginia Division, Fairfax County and City of Alexandria engineering staff. The TCT approved 92 percent of these recommendations. and rejected none. For example, the TCT approved the Telegraph Road Panel’s recommendations for avoiding impacts to commercial properties as well as the elimination of interchange traffic lights north and south of the Beltway. The remaining recommendations were not within the TCT’s approval authority, but the TCT forwarded them to the appropriate authorities.

The TCT forwarded 19 recommendations to the VDOT Chief Engineer. The final supplemental EIS states that these recommendations, based on the approval of the VDOT Chief Engineer, were incorporated into the design of the preferred alternative. Examples of these recommendations for the Telegraph Road Interchange included geometric changes in the quadrants of the interchange ramps, the addition of pedestrian access across Telegraph Road, and protected turn lanes at Huntington Avenue. For the US 1 interchange, the final EIS incorporated intersection modifications, pedestrian/bicycle connections, and Washington Street deck refinements.

Virginia Stakeholder Panel Members concluded their word in June 1999, and FHWA asked participants to complete a survey on their experience. Survey results showed that 60 percent felt that they had influenced the design, about 30 percent were unsure, and the remainder felt they had not influenced the project. In evaluating the consensus building goals of the process, 47 percent said that as a result of the process, they were willing to compromise on some points of the project design, while 42 percent said that their views on project design had not changed as a result of the panel process.

The Maryland Interchange Panel began meeting in April 1999 and provided its recommendations to the MSHA project manager. The Panel proposed lengthening several bridges over Oxon Hill Road to accommodate pedestrian/bicyclists, eliminating some of the proposed traffic signals, retaining a direct exit from the Outer Loop of the Beltway to Oxon Hill Road, and adding a grade separation at an existing at-grade crossing. These were approved by MSHA and included in the design.

Transportation Decision-making Process

A variety of teams led by FHWA composed the decision-making structure for completion of the design changes reflected in the 2000 supplemental NEPA documents. The teams included:

- A Project Leadership Team consisting of high level officials from FHWA, MSHA, VDOT, and DCDPW. This team’s role was to provide strategic decision making, policy direction, and performance review;

- A Project Management Team Project composed of managers from FHWA, VDOT, MSHA, and DCDPW. This team worked on site and provided integrated technical guidance as well as operational management;

- An Environmental Management Group (EMG), which was charged with the completion of the supplemental NEPA documents, securing necessary permits, and monitoring mitigation commitments. The EMG was comprised of environmental managers from the sponsoring agencies including staff of the FHWA Maryland and Virginia Divisions and the Eastern Resource Center, VDOT, MSHA, DCDPW, and USACE. The EMG began meeting regularly in May 1998 and its meeting minutes are maintained and available at the Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project Offices in Virginia and Maryland;

- The General Engineering Consultant Team (GEC), which supported the EMG. This was and remains an existing consortium of consulting firms that prepared design reviews, impact analyses, mitigation proposals, permit applications, and now supports project monitoring;

- A Virginia Technical Coordination Team (TCT) consisting of the VDOT Project Manager and Bridge Engineer, FHWA Project Manager, FHWA Virginia Division, Fairfax County, and City of Alexandria engineering staff. The TCT met 12 times from September 1998 through August 1999. The TCT was charged with providing direction on the design elements and project features associated with the refinements for the Virginia portion of the project as well as considering recommendations from the three Virginia Stakeholder Participation Panels;

- An Interagency Coordination Group (ICG) that was composed of over 20 natural resource agencies with many having associated permitting responsibilities. The ICG worked directly with the GEC and EMG on the identification and acceptance of mitigation measures; and

- The Design Review Working Group, as discussed above, conducted the bridge design competition as well as reviewed other design documents and treatment plans for potential impacts to historic and cultural resources.

Decisions on dredging and dredged material disposal were coordinated between the USACE‘s Baltimore and Norfolk Districts with input from VDOT, FHWA, USEPA, MSHA, the Maryland Port Administration, Maryland Environmental Services, and Maryland Departments of the Environment and Transportation. Maryland agencies were particularly involved in the dredging impacts of the project because the state of Maryland owned the majority of the Potomac River that fell within the project area.

Key Decisions

FHWA used its existing reevaluation procedures to decide whether to supplement the 1997 Final EIS. Although the outcome may have been clear simply based upon the reevaluation of the newly projected and much larger construction impacts, FHWA also factored into its decision the allegations from the ongoing litigation. FHWA recognized that a supplement would provide a head start in addressing these allegations in the event that Agency lost its appeal. Although an affirmative decision would raise budget and scheduling concerns, FHWA decided to turn its efforts into initiating a supplemental draft EIS based on this litigation strategy, coupled with the USACE’s strong position that it could no longer use the 1997 EIS for permit decisions because of the dramatic increase in dredging that was required.

A secondary but important decision that related to the initiation of the draft supplement was determining the scope of that document. Whether or not an appropriate range of alternatives had been analyzed was still a matter of public controversy and the subject of the ongoing litigation. FHWA continued to consider only a 12-lane structure on the basis that previously-considered alternatives did not meet the project’s purpose and need statement. FHWA also decided that the draft supplemental EIS would carry forward the preferred alternative from the 1997 final EIS and address the environmental impacts of design refinements and construction impacts. Based on this project management decision, the EMG focused on building consensus around redesigns, completing high quality impact analyses of redesign and construction impacts, and completing a comprehensive package of mitigation measures.

Lessons Learned

Success Factors

Open and Collaborative Approach Reinvigorated Participants and Problem Resolution

By the time FHWA informed the affected resource agencies that a draft and final supplemental EIS would be required, these agencies had already been working on the Wilson Bridge project for well over 10 years. The FHWA environmental manager assigned to prepare the supplements recognized and quickly addressed frustrations with the process and some distrust with the manner in which it had moved forward. FHWA assured the resource agencies that their concerns would be heard and all reasonable efforts would be made to accommodate their mitigation recommendations. Whenever a recommendation could not be accommodated, FHWA explained its reasons and was open to any follow up responses or modifications to the recommendation. This open, direct, and collaborative approach re-invigorated the participants and fostered a team approach to problem resolution.

This approach proved to be extremely beneficial when late in the NEPA process, after the publication of the draft supplemental EIS, FHWA and the resource agencies determined that it was necessary to consult on two potential endangered species impacts. One consultation occurred with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) regarding possible impacts to endangered Shortnose Sturgeon. The other consultation occurred with the FWS over possible impacts to the bald eagle, which was listed as an Endangered Species at the time. Based on a rapidly prepared FHWA biological assessment, NMFS concurred in a no adverse effect determination for the sturgeon. After preparing a biological opinion for the Bald Eagle, FWS concluded this consultation based upon acceptable project mitigation. The working relationships and professional trust that had been established between the agency representatives led to the resolution of sensitive endangered species impacts that might normally derail the project development schedule and create a media controversy.

Key Innovations

Comprehensive Project Mitigation

The ROD for the FSEIS contained numerous mitigation measures covering several pages. These measures ranged from some very specific requirements to concepts that required further analysis and consultation with the affected resource agencies. Mitigation requirements were divided between Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia based on the functions and types of permanent impacts associated with each jurisdiction. The requirements included the following:

- Installation of 22 fish passageways and one fish ladder on Rock Creek and Anacostia River tributaries to allow fish to spawn upstream of previous man-made barriers;

- Stocking of 15 million River Herring in Rock Creek and Anacostia River tributaries;

- Establishment of an 84-acre bald eagle sanctuary in Prince George’s County;

- Building of a fish reef in the Chesapeake Bay using thousands of tons of the old bridge;

- Preservation or creation of approximately 146 acres of wetlands at various locations in Virginia and Maryland;

- Planting of 20 acres of river grasses in the lower Potomac River for fish habitat and water cleaning purposes; and

- Preservation of more than 140 acres of woodlands in Prince George’s County.

An important question or concern from the public as well as the ICG was how FHWA would ensure that its complete list of requirements was actually implemented. FWHA took two important steps in response:

- First, FHWA included within the mitigation package a requirement for the designation of an independent environmental compliance monitor. The monitor reports directly and concurrently to the regulatory agencies and the sponsoring agencies on the status of FHWA’s compliance with the mitigation measures; and

- Second, with extensive technical assistance from the GEC, FHWA developed a system to track the numerous environmental commitments made during both the first and second project planning and development processes. The development and use of the tracking system was re-enforced by the Department of the Army Permit, Special Condition 5. As a major bridge project, the management of water-related impacts was a major undertaking. Special Condition 5 required the submission of interim and final tracking reports for environmental commitments, reports on instances of non-compliance, and a final report of total impacts to the Waters of the US.

Irrespective of the USACE’s permit requirements, the tracking system was a necessary management tool for the bridge development process because this was a highly complex project. For example, one contracting component of the bridge reconstruction was contract VA 5, for the reconfiguration of the interchange with US Route 1 in Alexandria. VA-5 was a $39 million sub-contract involving construction of 11 bridge structures to carry traffic over extremely sensitive areas including Cameron Run, Hunting Creek, and tidal wetlands and mudflats associated with the Potomac River. The planning process had entailed a great deal of effort to ensure that water quality was not adversely affected. The contractor had to remove the old causeways and accesses, which was a major challenge. The contract required 44 cofferdams, and each pumped discharge that needed treatment through sediment bags and turbidity curtains. The VA-5 sub-contract alone had 944 commitments designed to prevent impacts to the sensitive environmental resources of the area.

The database was maintained by the GEC as a monitoring tool for the Environmental Management Group. It was accessible to the resource agencies. The GEC monitored the database closely to ensure that the information was conveyed to the appropriate parties. Prior to an inter-agency meeting, such as the Design Review Working Group, or the preparation of permit plates for dredging activities, the GEC would go through the list of commitments to ensure their status was properly conveyed to the appropriate parties.

FHWA’s use of the tracking system was invaluable to the project development, permitting, and delivery processes. It became the repository of thousands of commitments and could be reviewed and updated at any time in response to project activities. It provided a method for ensuring that commitments were carried out. Furthermore, this tracking database now serves as a record of the mitigation process and is the basis for accurate and efficient reporting to permitting agencies and other interested organizations.

Barriers Encountered and Solutions

Interagency Coordination

FHWA faced a complex task in having to coordinate project planning between two states, the District of Columbia, all of their jurisdictional components, and several major federal agencies. In order to reduce the communication problems that could arise with so many parties involved, FHWA assigned key environmental and project management staff to the two project offices. It and assigned an FHWA attorney to work with this on-site staff on a continuing basis. Several representatives from involved resource protection agencies as well as the consulting consortium noted that this on-site presence was critical in both simplifying communications between all parties and obtaining timely guidance and decisions from FHWA.

FHWA also scheduled frequent meetings. The EMG and GEC met weekly to go over the status of unresolved impact issues as well as next steps. The ICG, the larger group of predominantly resource protection agencies, met at least monthly.

FHWA directed that minutes be recorded, distributed, preserved and made publicly available and accessible at the local project offices. The minutes also became the basis for tracking progress and the commitments made on a variety of issues. The federal government’s litigation team also relied upon the minutes to explain FHWA’s decision-making process to the court.

Litigation Management

During the initial months that FHWA prepared the SDEIS, the agency was still under the federal district court’s decision that it had violated NEPA, Section 106 of the NHPA, and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act with respect to the 1997 FEIS process. Nevertheless, FHWA chose to consistently maintain its position that only a 12-lane structure could meet the project’s purpose and need. Rather than reopening consideration of alternatives in the DSEIS and restating the purpose and need for the project, FHWA referred the reader back to the 1997 FEIS for the purpose and need statement. In so doing, FWHA was able to focus the remaining analytical work and extensive inter-agency coordination around its preferred alternative.

At the same time, FHWA was sensitive to both its position in the lawsuit and the related and continuing questions from the public on the feasibility of a tunnel alternative. In response, FHWA undertook a more thorough and documented analysis of a tunnel alternative and shared it with the public. FHWA did this to more fully and openly explain reasons why it did not believe that a tunnel was a reasonable alternative. FHWA also included the tunnel study as an appendix in the SFEIS rather than in the body of the document. In its ROD for the FSEIS, FHWA concluded that any benefits to a tunnel were greatly outweighed by the substantially greater environmental impacts, costs, operational issues, and constructability challenges of this alternative.

This litigation strategy proved highly successful as the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia agreed with FHWA’s position that for an alternative to be considered within the range of the reasonable alternatives, it must meet the purpose and need for the project. The Court found that FHWA need not consider alternatives in detail that do not meet the Agency’s transportation goals for a project. This decision was of great value as a precedent in FHWA’s NEPA program because it rejected earlier judicial interpretations of NEPA as requiring even unreasonable alternatives to be considered in an EIS and it came from such an influential federal court.

Merger of NEPA and USACE’s Permitting Requirements

When FHWA announced its decision to start the supplemental EIS process, it also committed to completing the process and required project permitting as expeditiously as possible. FHWA worked very closely with the USACE to achieve this result. For example, FHWA used the SDEIS as its initial permit application to the USACE. FHWA and USACE held joint public meetings for NEPA and permitting purposes. The SFEIS served as the final permit application. Both agencies concurred in and used the SFEIS as their NEPA compliance documents for their independent federal actions. FHWA signed its ROD in June 2000 and the USACE issued its permits approximately two weeks later.

Unanticipated Construction Impacts

The low estimates of the dredging impacts in FHWA’s 1997 FEIS and the resulting inability of the USACE to adopt that EIS were major reasons why FHWA decided to prepare another draft and final EIS. When preparing an EIS in the early stages of the project development process, it is particularly difficult for teams of planners and design engineers to quantify construction impacts. All of the specific construction, staging, materials, and disposal sites may not be known and the team may not have sufficient construction expertise. This project highlights the need to include that expertise to the fullest extent possible.

Memoranda of Agreement Are Valuable Tools

As previously mentioned, FHWA entered into an MOA for the purpose of complying with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. In addition to establishing the design review goals for the bridge, the MOA established procedures for evaluating and treating cultural resources. FHWA was able to use these flexible procedures to effectively stage its compliance rather than having to have complete identification and treatment of all sites prior to the start of construction and as long as the deferred sites were not yet subject to construction activities. A contributing factor to this effective approach was the GEC’s cultural resource experts, who were highly experienced in the Section 106 process and credible to the resource agencies.

Documenting Pre-Construction Conditions

As part of the comprehensive mitigation package for the project, FHWA promised that the two cemeteries on the Virginia side and very near construction sites would not be adversely disturbed. Prior to construction, headstones at St. Mary’s cemetery showed deterioration that appeared to be the result of their age. To ensure that the headstones were not later considered to be harmed by construction, FHWA conducted two full assessments of the more than 2,000 markers and other structures, resulting in the preparation of extensive notes and over 10,000 digital images. FHWA placed vibration monitors above and below ground and conducted pedestrian monitoring of standing structures and ground disturbances. Weekly monitoring indicated that no damage was occurring that could be correlated to bridge construction activities. In order to confirm this understanding, after pile driving and completion of most of the Route 1 interchange, FHWA conducted a second assessment of the cemetery and made comparisons to the previous assessment.

Creative Dredge Material Disposal

Once FHWA quantified dredging requirements, off-site disposal of the dredged materials became a serious problem. After the EMG and GEC evaluated almost 20 disposal sites, the GEC found a disposal site at Port Tobacco in Weanack, Charles County, Virginia, to be acceptable on the basis of cost and acceptance of wet dredged material (Figure 6). This site is located on an 800-acre tract containing Shirley Plantation, which is a designated National Register and a National Historic Landmark site. As a result, approximately 500,000 cubic yards of unwanted dredged material served to stabilize and restore the previous agricultural use and appearance of the historic Shirley Plantation.

Summary

Summary

Ten years into the Woodrow Wilson bridge project development process, FHWA successfully faced the challenges of re-starting the NEPA and Section 404 permitting processes while minimizing further delays in the start of the bridge’s construction. FHWA accomplished this by:

- Assembling a highly qualified team of federal and state project managers and environmental impact review staff;

- Securing excellent consultants;

- Effectively collaborating with the USACE, other key resource agencies, and the most affected public;

- Developing consensus around a context sensitive bridge design;

- Coordinating its litigation strategies with the scope of its ongoing NEPA analyses; negotiating a comprehensive set of mitigation requirements; and

- Establishing a transparent monitoring program for those requirements.

Sources

Stakeholder Participation Panels In the Public Involvement Process, prepared for Federal Highway Administration by Potomac Crossing Consultants, November 1998.

Settlement Agreement Between The City of Alexandria, Virginia And The United States Department of Transportation, March 1, 1999.

City of Alexandria, Virginia, et al., Appellees v. Rodney E. Slater, Secretary, U.S. Department of Transportation, et al., Appellants, United States Court of Appeals For the District of Columbia, Opinion Number 99-5220, December 17,1999.

Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement/Section 4(f) Evaluation, Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project, prepared by U.S. Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration, Virginia Department of Transportation, Maryland Department of Transportation, State Highway Administration, and District of Columbia Department of Public Works, April 4, 2000.

Record of Decision, Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project, prepared by U.S. Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration in cooperation with Virginia Department of Transportation, Maryland Department of Transportation, State Highway Administration, and District of Columbia Department of Public Works, June 16, 2000.

Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project Overview, prepared for U.S. Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration, Virginia Department of Transportation, Maryland Department of Transportation, State Highway Administration, and District of Columbia Department of Public Works by Potomac Crossing Consultants, 2007-2008.