US Department of Transportation

FHWA PlanWorks: Better Planning, Better Projects

| Framework Applications |

|---|

NJ Route 31 Integrated Land Use and Transportation Plan

New Approach to Highway Capacity Expansion Consistent with Smart Growth and New Jersey Future in Transportation (NJFIT)

Executive Summary

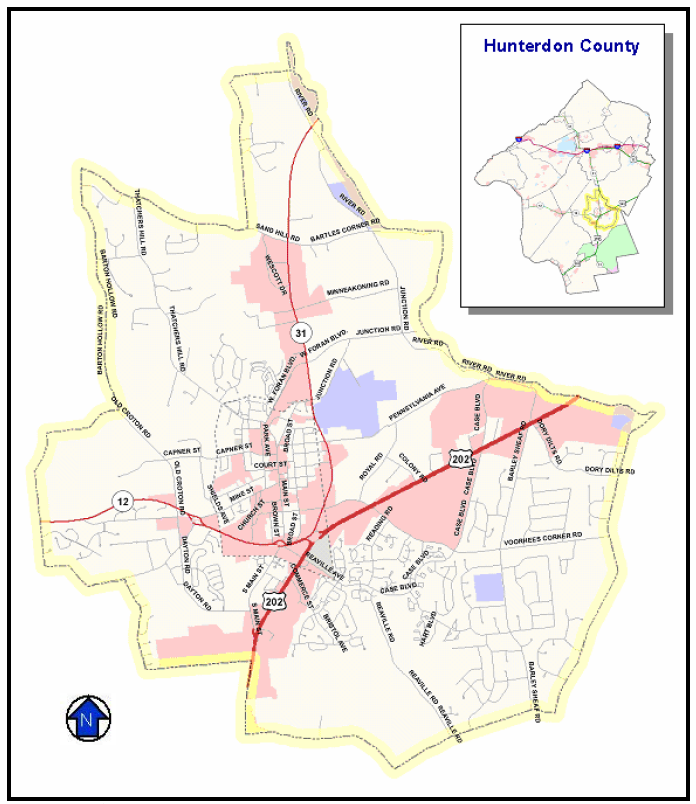

Hunterdon County, which sits on New Jersey’s western border with Pennsylvania, was historically a rural area. However, due to its proximity to both the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan areas, the county has been attracting commuters and has experienced both residential and commercial development. Route 31, which bisects the county, is one of the few north-south connections in that part of the state and thus serves an important role in regional and interstate travel.

Route 31 passes through Flemington Borough, which is the county seat and its oldest community, and Raritan Township, which encircles the borough. Congestion along Route 31 in these communities has been a concern for decades, and for much of that time, a grade-separated, multi-lane highway bypass running east of Flemington through Raritan Township has been forwarded as the preferred solution to the problem. The New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) even received federal funds to begin acquiring the proposed right-of-way for the bypass before it was developed.

In 2003, NJDOT was in the process of preparing a Draft EIS for the most recent design of the long-proposed “Flemington Bypass” when several factors led to yet another re-examination of the corridor. One factor was the project’s inconsistency with the state’s newly issued smart growth principles. A second factor was the relatively high cost of the bypass (roughly $125 million to $150 million) compared to the availability of state highway funding. A third factor was growing concern in the community about the possible negative impacts of the bypass on the local business community and the area’s environmental resources.

In response, NJDOT embarked on one of its first efforts to integrate land use and transportation planning. NJDOT engaged the local governments and other stakeholders in a highly collaborative planning process that produced both a transportation solution and a set of recommended land use changes. During this process, the project team overcame the community’s initial distrust of and anger toward NJDOT, as well as skepticism that the proffered smart growth alternative could actually accommodate the increasing levels of traffic projected for the area.

In November 2006, NJDOT initiated the EIS process for the South Branch Parkway, the primary roadway component of the integrated plan that resulted from this planning process. Raritan Township and Flemington Borough continue to work on implementing the land use component of the plan. Raritan Township began revising its master plan in the fall of 2007 and will consider incorporating the land use recommendations from the plan during that process.

The major lessons learned from this planning process include:

- Local decisions regarding land use and the local road network can significantly reduce the traffic burden on state highways;

- Identify and enlist local champions; if local leadership is lacking, cultivate it through capacity building or other assistance;

- Adapt the planning process itself to the needs of the participating community; and

- Trust is essential for effective collaboration to occur, and it may take time and resources to develop that trust.

Background

Hunterdon County is an exurb on the western edge of New Jersey, about one hour from both the Philadelphia and New York metropolitan areas. This proximity accounts for the county’s evolution from a rural area into a bedroom community for commuters, an evolution that has exacerbated congestion on Route 31 in Raritan Township and Flemington Borough, the historic centers of growth in the county.1 In addition to providing local access to a commercial district, a major medical facility, schools, and neighborhoods, Route 31 is one of the few regional north-south connections in this part of New Jersey, making it an attractive route for regional traffic. In addition, the convergence of Routes 31, 202, and 12 at the Flemington Circle just south of the Flemington Borough contributes to increased congestion and has raised safety concerns.

Project Overview

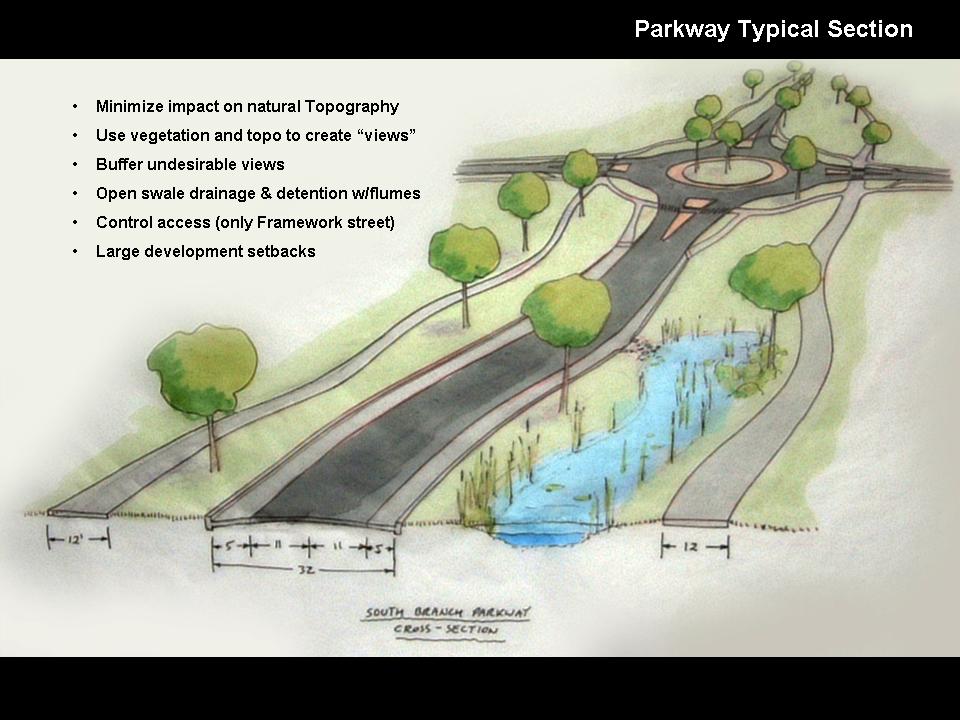

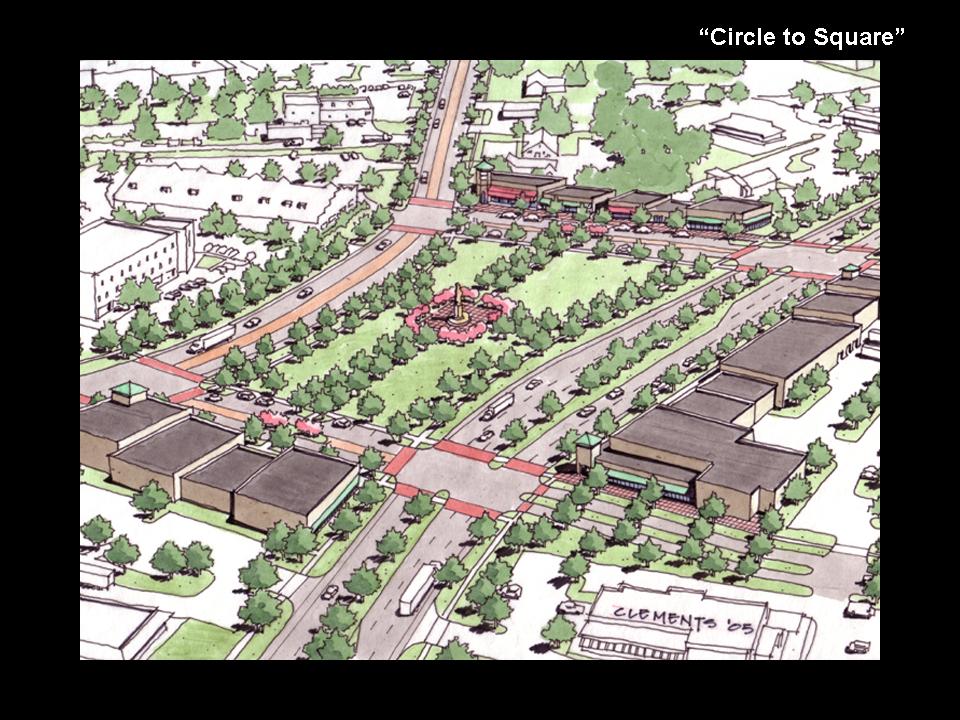

The Route 31 Land Use and Transportation Plan includes a number of roadway changes along the Route 31 corridor through Flemington Borough and Raritan Township. First, the plan includes a new, at-grade parkway (known as the South Branch Parkway) that would serve as a regional alternative to existing Route 31. Second, the plan envisions a new network of local roads along with sidewalks and other amenities to encourage pedestrian and bicycle movement throughout the area. Third, the plan includes the “untangling” of Flemington Circle, which is where Routes 31, 202, and 12 currently converge. Under the plan, the circle would be converted into a series of streets and blocks.

Taken together, the components of the Route 31 Land Use and Transportation Plan are intended to distribute the area's traffic (both local and regional) to a larger number of streets and intersections in an effort to avoid focusing too much traffic at any one location. The new road layout is also intended to provide better access to existing businesses, industries, and future development sites. In addition, the proposed parkway will serve as a clear boundary between the area's urban and suburban development and its remaining rural land. Finally, the plan promotes a recreational and historic greenway corridor to preserve and celebrate the historic and environmental resources along the South Branch River.

Project Drivers

Since 1987, NJDOT has studied a number of congestion mitigation alternatives for this stretch of Route 31. For much of that time, a four-lane, controlled-access bypass (known as the Flemington Bypass), complete with grade-separated interchanges, was planned for the land east of Flemington through mostly vacant, industrial-zoned land. NJDOT even began acquiring land along the proposed right-of-way with funds from a Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) pilot program for corridor preservation.

Figure 1. Corridor Study Area for the Route 31

Integrated Land Use and Transportation Plan

Source: Traffic Analysis Summary Final Report for the NJ Route 31 Integrated Land Use and Transportation Framework Plan, March 2006 (revised May 2006).

Several trends converged to prompt a re-examination of the bypass in late 2003, the first of which was heightened interest in smart growth among the state’s leaders and policymakers. In 2002, Governor James McGreevy established a set of smart growth principles for the state and created a Smart Growth Policy Council to ensure that statewide programs and projects were consistent with the state’s smart growth principles. The new council consisted of statewide departments and agencies, including NJDOT.

Smart Growth Principles

- Mixed land uses

- Compact, clustered community design

- Range of housing choice and opportunity

- Walkable neighborhoods

- Distinctive, attractive communities offering a sense of place

- Open space, farmland, and scenic resource preservation

- Future development strengthened and directed to existing communities using existing infrastructure

- Variety of transportation options

- Predictable, fair and cost-effective development decisions

- Community and stakeholder collaboration in development decision making

Source: NJ Office of Smart Growth Website

Consistent with this new emphasis on smart growth and realizing the long-term fiscal and other limits on the state’s ability to grow out of congestion via highway expansion, NJDOT, under the leadership of Commissioner John Lettiere, began changing its approach to congestion relief.

On the smart growth side, NJDOT concluded that the conventional strategies (e.g., additional lane-miles and grade-separated interchanges) were spurring growth, which was quickly negating the congestion relief gained from additional highway capacity. NJDOT decided that it needed to engage local governments and work with them to develop land use and transportation policies that would break the cycle between increasing highway capacity and sprawl.

The second trend prompting the re-examination of the NJDOT’s conventional approaches was related to the cost of road widening relative to the benefits provided. The cost of highway construction continues to increase, and state transportation funding is already stretched thin. Furthermore, road widening requires taking homes and businesses in many areas. NJDOT decided that it could no longer afford to build costly highway capacity projects that would provide congestion relief for only a few short years. The agency adopted a philosophy that the state’s limited transportation funds should be prioritized for communities that were willing to adopt land use plans that would preserve the utility of the state’s investment.

The combination of these trends led to NJDOT’s decision to set aside the long-proposed Flemington Bypass and to undertake an integrated planning process for Route 31 that addressed both land use and transportation. In the midst of this planning process for the Route 31 corridor, NJDOT institutionalized this new approach to transportation planning by creating the Future in Transportation (FIT) Program.

Major Project Issues

Congestion

Hunterdon County’s proximity to the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan areas has made it attractive as a bedroom community. Suburban commercial development has followed the influx of new residents. This development, combined with the lack of other north-south alternatives for both local and regional trips has led to significant levels of congestion on Route 31.

Community Impacts of Growth

In addition to congestion, local residents were also concerned about how growth was affecting the county’s open space, its agricultural resources, and its “small town feel.” Much of the land in Raritan Township near the proposed route of the Flemington Bypass was zoned for industrial use, but at the time there was not a strong demand for that type of land. Therefore, the land essentially served as open space, unless the township had granted a zoning exception permitting other types of land uses. Some members of the community were concerned that a re-examination of local zoning might accelerate the development of the township in ways that would further harm the quality of life in the area or overwhelm public services such as schools and sewers.

Cost

As described above, NJDOT deemed the Flemington Bypass no longer cost-effective. In addition to finding an alternative that was more consistent with the state’s smart growth principles, the NJDOT also needed to find a more affordable alternative.

Community’s Lack of Trust in NJDOT

A major issue at the outset of the planning process was the frustration and distrust felt by many members of the local community. Some local residents considered NJDOT’s decision not to proceed with the Flemington Bypass after decades of study a betrayal or a broken promise. To make matters worse, NJDOT was proceeding with a project integrally linked to the bypass, the replacement of the nearby Flemington Circle with a grade-separated interchange. That project, which was in the final design stage at the time, was opposed by some residents and many local business owners. Overall, the community was concerned that NJDOT was not interested in hearing their opinions and working with them to develop a locally supported alternative to the Flemington Bypass.

Institutional Framework for Decision Making

As with other corridor studies it conducts, NJDOT retained decision-making authority throughout the planning process. Because of the work that had already gone into the yet-to-be-published Draft EIS for the Flemington Bypass, NJDOT decided not to structure the corridor study to accomplish NEPA objectives. The agency’s intention at the time was to revise the Draft EIS for the Flemington Bypass based on the results of the corridor study.

The planning boards of Raritan Township and Flemington Borough had implementation authority for the land use component of the plan. Therefore, from the start NJDOT committed itself to collaborating with members and staff of the local planning boards, as well as with local elected officials. To help structure the feedback it received from the community, the project team created an advisory entity whose membership was expanded midway through the planning process.

Figure 2. New Roads Proposed as Part of the Route 31

Integrated Land-Use and Transportation Plan

Note: Solid black line is the proposed South Branch Parkway. Dotted black lines are proposed local roads. Source: Traffic Analysis Summary Final Report for the NJ Route 31 Integrated Land Use and Transportation Framework Plan, March 2006 (revised May 2006).

An initial project Advisory Group was formed that included representatives from NJDOT, FHWA, Raritan Township, Flemington Borough, Hunterdon County, and local business associations. The representatives of the local and county governments included both elected officials and technical staff from the planning boards and engineering departments. In addition to conducting one-on-one interviews with local stakeholders and conducting design workshops, the project team met twice with this Advisory Group during the development of an initial “Framework Plan.” The Framework Plan was then the starting point for a broader planning process with public meetings and more stakeholder input.

During this second stage of the planning process, the Advisory Group was expanded and renamed the Local Planning Committee. The project team added two elected representatives of Hunterdon County (known as freeholders), several representatives of the New Jersey Office of Smart Growth (part of the state’s Department of Community Affairs), and representatives of different offices within NJDOT. In addition, the team invited the participation of a planner from the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, the federally authorized metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for Hunterdon County and the 12 other counties in northern New Jersey.

Other federal and state agencies were invited to participate but did not do so. According to members of the project team, this lack of participation was one of the more disappointing aspects of the planning process. However, the federal and state resource agencies had participated in the development of the Draft EIS for the Flemington Bypass, so their concerns in the planning area were already known to some extent.

The Local Planning Committee was not given any formal decision-making authority, but it did provide feedback on new project information, studies, and analyses as the planning process progressed. The committee had four subcommittees, which worked with the project team on specific components of the plan:

- Public Outreach

- Network Traffic Modeling

- Access Management

- Land Use Market Study and Fiscal Impact Analysis

Decision-making Process

NJDOT began conducting congestion studies on this corridor in 1987. Among the alternatives studied was a four-lane, limited-access highway bypass connecting Route 31 with Route 202. Over time, this “Flemington Bypass” was deemed the most effective way of reducing congestion pressures throughout the project area. The MPO for Hunterdon County, the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, added the project to the region’s long-range transportation plan. In an effort to curtail development in the proposed corridor of the bypass, FHWA included the project in a pilot program for corridor preservation. As a result, NJDOT was ultimately able to acquire approximately 40 percent of the proposed right-of-way.

The Draft EIS for the bypass underwent internal review at NJDOT in the fall of 2003. The review committee sent the Draft EIS back to the Division of Project Planning and Development, citing its inconsistency with the state’s smart growth principles. The State of New Jersey had recently established a set of statewide smart growth principles to which all state agencies were required to adhere. There was also growing recognition within the NJDOT that the proposed bypass (estimated to cost $125 million to $150 million) had become too expensive to build.

The Division of Project Planning and Development, headed at the time by Gary Toth, convinced NJDOT’s senior management that it could work with the community to develop an alternative to the Flemington Bypass that would both cost less and be more consistent with the state’s smart growth principles. NJDOT engaged the community planning and design firm Glatting Jackson Kercher Anglin (Glatting Jackson), along with local planning and engineering firm McCormick Taylor, to work with the community to develop this alternative.

Early on in the planning process, Raritan Township and Flemington Borough accepted the offer of Donna Drewes from the Municipal Land Use Center to act as a facilitator during the planning process and to assist with public outreach. The center, funded by an FHWA grant, had been recently established to support local and county governments in a five-county area through training, data-sharing, conflict resolution, and other technical assistance. The mission of the center is to encourage new development and redevelopment patterns that produce communities that are more compact, walkable, aesthetically attractive, and less dependent on automobiles.

Development of the Framework Plan

The planning process used by the project team did not follow the conventional sequence of transportation planning; e.g., defining purpose and need, establishing evaluation criteria, developing alternatives, and evaluating alternatives. On the transportation side, the process was designed to gauge the acceptability of a specific transportation solution (i.e., a parkway plus an extended local road network) and to make decisions about the details of the solution (e.g., how many new local roads and where to build them). According to members of the project team, previous studies had considered and eliminated numerous alternatives, so NJDOT decided that it was not necessary to study any of them again. On the land use side of the planning process, however, the development of alternatives was more robust.

The project team utilized several methods to learn about local issues and to shape the initial planning concept:

- Stakeholder Interviews. The project team conducted one-on-one interviews with stakeholders such as property owners, developers, interest groups, and local governments (both elected officials and technical staff). These interviews provided valuable insights into site-specific development issues and the interests of local jurisdictions.

- Advisory Group. The project team also created an Advisory Group that included representatives from NJDOT, FHWA, local governments, and local business associations. This group was later expanded and renamed the Local Planning Committee.

- Design Workshops. To facilitate both the stakeholder interviews and Advisory Group meetings, the project team held multi-day design workshops. These workshops, which included stakeholder interviews, site visits, and working sessions, created a “studio” environment that helped the project team test design ideas and continue to learn about local priorities and issues.

The project team conducted two sets of multi-day design workshops and meetings, first with a relatively small group of key stakeholders and second with the community at large. The initial planning activities, which took place in the spring of 2004, were intended to build consensus among NJDOT, area elected officials, technical staff, and key stakeholders around a conceptual alternative to the Flemington Bypass that addressed both transportation and land-use in the corridor. This conceptual alternative then served as the starting point for a second round of interactions with the community at large.

The conceptual transportation alternative needed to meet the following criteria:

- Sufficiently manage congestion;

- Be consistent with New Jersey’s smart growth principles;

- Be cost-effective; and

- Support the local goals of Raritan Township and Flemington Borough.

It was during the initial interactions with the community that the project team learned of the anger and distrust that members of the community felt toward NJDOT. These feelings stemmed in part from the long and seemingly fruitless wait for the Flemington Bypass. Residents felt that NJDOT had broken a long-held promise to provide a solution to the community’s traffic congestion. Adding to the residents’ resentment was the delay in NJDOT’s completion of an intersection improvement project on Route 31. Lastly, as described in more detail below, some residents and local business owners were opposed to NJDOT’s planned replacement of the nearby Flemington Circle with a grade-separated interchange.

According to interviewees, NJDOT and its consultants were able to rebuild trust with the community by proving that they were truly interested in obtaining community input for the design of the substitute for the bypass. In addition to holding public meetings and sessions with the advisory bodies it created, NJDOT and its project team held many one-on-one interviews with residents. Members of the project team also attended meetings of the governing bodies of Flemington Borough, Raritan Township, and Hunterdon County to receive feedback. To help convince residents that the agency was truly interested in helping the community, NJDOT also fast-tracked two small improvement projects along Route 31. The agency’s eventual change in course regarding the proposed replacement of the Flemington Circle also helped win over local residents and officials.

The project team released a Draft Concept Development Workbook in July 2004 that described the Framework Plan that resulted from the first set of interviews and design workshop. The workbook summarized the regional context for the corridor, including existing land use and zoning. It laid out the local land use and transportation priorities that had been communicated by stakeholders and proposed the following transportation and land use changes:

- An at-grade parkway (known as the “South Branch Parkway”) that would provide a regional alternative to existing Route 31 but also would interconnect with existing and proposed local streets. This parkway would generally follow the proposed route of the Flemington Bypass;

- An expanded local street network that would take vehicles off of major roads by providing alternative routes for local trips;

- Zoning changes that would convert industrial-zoned land to other uses and use the parkway as a defining edge for future development; and

- Transformation of the South Branch River corridor into a greenway linking the community’s cultural and historic resources.

Expansion of the Project to Include the Flemington Circle

Figure 3. View of Flemington Circle Looking Northeast

Source: Route 31 Land Use & Transportation Plan: Concept Development Workbook (Draft), July 2004.

An important development occurred during the first phase of this planning process. NJDOT had initially limited the study area so that it excluded the Flemington Circle, which is located southeast of Flemington’s historic downtown and serves as the junction of Routes 12, 31, and 202. At the time of this planning process in 2003, NJDOT had already advanced to the final design stage of a project to eliminate the Flemington Circle by constructing a grade-separated interchange. The managers for the Route 31 planning process initially intended to assume construction of the grade-separated interchange and not to include the area around the circle in the study area.

However, local elected officials and members of the community repeatedly brought up the circle elimination project during meetings and interviews with the Route 31 project team. Some said that the community had been told that if it wanted the bypass, it had to agree to the grade-separated interchange. Residents argued that because the bypass project had been scuttled, NJDOT should revisit the need for the interchange.

Growing recognition of the relationship of the circle elimination project to the ongoing corridor study led to formal action by the three local governments. In June 2004, the Borough of Flemington issued a resolution requesting that NJDOT study alternative designs for the circle elimination project.2 By September 2004, Raritan Township and the Hunterdon County Board of Freeholders had also gone on record asking NJDOT to place the circle elimination project on hold until the land use and transportation plan was completed.3 The united display of opposition from the local governments eventually convinced NJDOT to put the final design of the circle elimination project on hold in late 2004. The Route 31 project team was then able to include the circle and its surroundings in the study area.

Refinement of the Framework Plan

For the second phase of the planning process, the project team expanded the Advisory Group and renamed it the Local Planning Committee. Several more local elected officials and planning board members were invited to participate on the committee. Also added were representatives from several offices within NJDOT and representatives of the New Jersey Office of Smart Growth. Beginning in September 2004, the committee met five times over 15 months to evaluate new project information, studies, and analyses. In addition to having the committee meetings, the project team held two public design workshops, one in November 2004 and another in March 2005. These workshops provided opportunities for interested citizens to work one-on-one with project team members and to offer their opinions and concerns.

The planning firm Glatting Jackson brought a team of urban designers and artists to these design workshops. This team was able to turn stakeholder input provided at these workshops into maps or other visualizations practically overnight (see Figure 4). Those participants who had been involved in similar studies said that they typically expect to wait several weeks to see stakeholder input fashioned in this way. Workshop participants asserted that this rapid production of visual aids was very important to the development of consensus around a preferred alternative.

|

Figure 4. Samples of Visualizations Developed During Design Workshops |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Glatting Jackson |

Traffic Modeling

Early on, the project team realized that it would need to assure the community and offices within NJDOT that the Framework Plan could address the area’s congestion problem over the long run. The team decided to develop a travel demand model and to simulate the long-term performance of the Framework Plan and other alternatives. Rather than rely on traditional demand modeling, NJDOT used a network simulation model that allowed participants in the planning process to see in real time how different land use and network scenarios would affect mobility in the region.

Figure 5. Non-Residential Zoning in

Raritan Township and Flemington Borough

Source: Route 31 Land Use & Transportation Plan:Draft Concept Development Workbook, July 2004.

Initial results from the modeling effort showed that the road network in the Framework Plan was feasible and could be designed and operated to achieve acceptable levels of service. As the planning process continued, the consultant modeled the long-range performance of three variations of the Framework Plan as revised by the Local Planning Committee in November 2005. These alternatives differed in the number of lanes for the proposed South Branch Parkway (two or four travel lanes) and number of lanes for Route 31 (five lanes or the existing roadway that had a varying number of lanes). The fourth main alternative was a no-build alternative.

The modeling showed that the three build scenarios would provide comparable levels of service in 2025 and would avoid the widespread queuing and travel delays seen in the modeling of the no-build alternative.

To answer questions about the performance of the Framework Plan if some of the additional local roads were never built, the consultant also modeled three variations of the local road network. For two of these variations, individual local roads were dropped from the Framework Plan. The third variation consisted of a four-lane South Branch Parkway with no additional local roads. Modeling of these network variations showed that removing individual local roads from the Framework Plan would result in overall degradation in traffic operations in the study area but would not cause any “fatal” impacts. According to the modeling results, building the South Branch Parkway without any of the local roads in the Framework Plan would lead to failing levels of service and major queuing along US Route 202.

According to interviewees, the traffic modeling results played an important role in convincing members of the community and offices within NJDOT that the Framework Plan was feasible and could be designed to achieve acceptable levels of service.

Land Use Market Study and Fiscal Impact Analysis

One of the concerns residents raised during the planning process was that rezoning would financially overburden Raritan Township and the two area school districts. To give the community a better understanding of the future implications of its land use decisions, the project team commissioned a market study and fiscal impact analysis. The purpose of the market study was to compare development trends in the region with Raritan Township’s current zoning. The fiscal impact analysis was intended to show the impact of different development scenarios on projected tax revenues and on the cost of public services and infrastructure. The real estate advisory firm Robert Charles Lesser & Co. initiated these two analyses in February 2005 and presented its findings to a joint planning commission meeting in November 2005.

Transportation Program

The Route 31 Land Use and Transportation Plan is just one of several integrated land use and transportation plans that have been advanced by NJDOT’s Future in Transportation (FIT) program.

The program, which was initiated in early 2005, works with communities to improve mobility by creating better connections among existing and future local roads so that drivers can take more trips without using the state highway system. NJDOT is also providing planning assistance and consultant resources to local governments to help them develop transportation and land use plans that make transit, bicycle, and pedestrian travel a more viable choice.

In partnership with other state agencies, the state’s three MPOs, and local governments, NJDOT has already been able to downsize alternatives, increase transportation options, lower design speeds, and provide more pedestrian-friendly streetscapes in several projects around the state.

Source: NJ FIT Website, http://www.state.nj.us/transportation/works/njfit/

The market analysis was based on regional growth trends, targeted interviews with local real estate professionals, and statistical demand analysis. At the time, most of the land between Route 31 and the South Branch of the Raritan River was zoned for industrial use, and much of this land was either undeveloped or under-developed. The market analysis concluded that the current market for this type of land use was so weak that the more than 800 acres of land available represented between 75 and 115 years worth of supply.4 In contrast, the market analysis identified strong demand for primary housing of all types, including age-restricted (i.e., “empty nester” or “move down”) housing, which would not tax the capacity of the area’s schools.

The consultant conducted the fiscal impact analysis in cooperation with the budget personnel of Raritan Township and the two school districts in the area. The result of this study was an estimate of revenues and costs of different types of development to the township and the school districts. Projected revenues were driven primarily by property taxes, while expenditures were generally based on the projected number of residents, employees, and students. The study informed the community of the likely fiscal impacts of different land uses on the township and the school districts. Most importantly, the study found that there was enough capacity in the sewer and school systems to allow some residential development without triggering the need for large capital investments.

The analysis then identified 25 parcels in the project area for which the existing land use was considered obsolete or undervalued for that location, or, if vacant, the existing zoning might not result in the most appropriate use. The analysis then demonstrated different mixes of proposed uses, originally arranged thematically: residential, industrial, open space, and a hybrid mix. Over time, the project team, in consultation with the Local Planning Committee and the local planning boards, developed several more hybrid alternatives. These alternatives were run through the traffic model to make sure that adequate levels of service were maintained.

As shown in Table 1, the final land use plan proposed changing from predominantly industrial and commercial zoning to a more balanced mix of land uses:

Table 1. Comparison of Permitted and

Proposed Land Uses in Raritan Township

Land Use |

Current Zoning |

Proposed Zoning |

|---|---|---|

Residential |

9 acres |

286 acres |

Industrial |

728 acres |

250 acres |

Retail/Office |

329 acres |

264 acres |

Open Space |

0 acres |

266 acres |

Total |

1,066 acres |

1,066 acres |

Source: Route 31 Transportation and Land Use Plan (land use component), prepared by McCormick Taylor, draft dated June 1, 2007.

The New Jersey Office of Smart Growth supported these land use planning activities by providing a $150,000 planning grant to Raritan Township and Flemington Borough. The township used its share of the grant to further evaluate and refine the land use plan. The borough used its portion to develop historic design guidelines for its downtown.

Current Status of Plan Implementation

The South Branch Parkway is the first transportation component of the plan to be implemented. FHWA issued a Notice of Intent for an EIS for the parkway in November 2006. NJDOT had been hoping it could continue the EIS process for the Flemington Bypass. However, FHWA required the agency to start over again using the revised environmental review process put in place by the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU), which was enacted in August 2005.

Because NJDOT had studied the Flemington Bypass for decades and had considered and rejected numerous alternatives, the agency had been planning to consider only two alternatives in the EIS: (1) constructing a new two-lane, limited access parkway as detailed in the Integrated Land Use and Transportation Plan; and (2) taking no action. However, representatives of the resource agencies (many of whom are new to the project) expressed an interest in seeing more alternatives, so it is likely that at least four alternatives will be considered.

NJDOT intends to include the local road network proposed in the Framework Plan in the EIS analysis of indirect and cumulative impacts rather than as part of the parkway alternative. However, other agencies have argued that the alternatives should include the local road network as part of the proposed action. If the local roads are left out of the build alternatives, NJDOT will only have to mitigate for the environmental impacts of the parkway. On the other hand, the modeling study predicted adverse traffic impacts without local roads. If the local roads are left out of the build alternatives, then resource agencies and the public may comment that mitigation proposed in the EIS is inadequate. This would put pressure on NJDOT to fund or undertake additional improvements to local roads and intersections.

The local road network envisioned in the Integrated Land Use and Transportation Plan will be built as development occurs. NJDOT is implementing some design changes along Route 31 and elsewhere in the study area to help alleviate congestion and improve safety in the short-term.

The Framework Plan proposed converting the Flemington Circle into a town square. However, due to current traffic patterns and volumes, the conversion cannot be completed until the opening of the South Branch Parkway. Because of ongoing congestion issues and safety concerns, NJDOT is conducting a feasibility study to investigate converting the circle to a multi-lane roundabout as an interim solution.

Raritan Township and Flemington Borough continue to work on the land use component of the plan. Raritan Township began revising its master plan beginning in the fall of 2007 and will consider incorporating the land use recommendations from the plan during that process. Flemington Borough is still finalizing its historic design guidelines and has not yet decided whether to incorporate any of the guidelines into its local ordinances. There are a significant number of developable parcels in the Flemington and Raritan study area. Coordination with these developers is ongoing to ensure compatibility of their plans with the Framework Plan.

Lessons Learned

The Route 31 plan was one of NJDOT’s first integrated land use and transportation plans. Based on the success of this and other integrated planning efforts, NJDOT has institutionalized this planning approach in its Future in Transportation (FIT) program.

Success Factors

State and Local Champions for Study

Several interviewees gave much of the credit for the success of the planning process to Gary Toth, who headed NJDOT’s Division of Planning and Project Development at the time. Toth was a strong proponent within NJDOT not only for the Route 31 study but also for context sensitive solutions and integrated planning. He helped to institutionalize these approaches in the agency’s FIT program, which he directed until his retirement in June 2007. Through the program, NJDOT forms partnerships with communities to coordinate land use development and redevelopment with transportation needs and investments. The Route 31 study is one of the earliest projects associated with the FIT program.

“Flexibility should be a feature of modern planning and project development…the planning process itself needs to be context-sensitive and adapted to the local community.”

— Ian Lockwood,

Glatting Jackson

Local advocates were also cited as instrumental in the success of the planning process. A few key officials from both Raritan Township and Flemington Borough were credited with actively encouraging the participation of fellow politicians and other community leaders. This feat was more impressive considering the previous lack of cooperation between Flemington Borough and Raritan Township on planning issues. To foster collaboration when local leadership is lacking, state DOTs will need to cultivate leaders in the community.

Flexible Process Adapted to Meet Needs and Issues as They Arose

Members of both the project team and the Local Planning Committee described the planning process used as relatively “fluid” and “flexible” and said that this characteristic contributed to the project’s success. According to members of the project team, the process was not planned out in detail beforehand; rather, the team was able to adapt the process to meet needs and address issues as they arose. For example, the project team undertook the fiscal impact analysis to resolve residents’ concerns that zoning changes in Raritan Township would overwhelm the township’s ability to provide public services.

Part of the reason for this flexible approach was that this study was an early attempt by NJDOT to integrate transportation and land use planning. The agency had not yet created a formal process for this type of study. However, this style of adaptive management is also an intentional characteristic of the planning approach used by the consultant.

While the lack of a formal decision-making structure or process was deemed to be an asset in this case, some participants suggested that future studies of this kind should use a document that establishes ground rules and spells out responsibilities of the various actors.

Key Innovations

Unfettered State Assistance for Local Land Use Planning

The Route 31 planning process was aided greatly by the use of state funds to support local planning efforts. Participants in the process noted that it was important that the grant funding made available to the local planning boards was “hands off” and that the outcomes of the funded activities were not foreordained by NJDOT or the Office of Smart Growth.

Fiscal Impact Analysis

The fiscal impact analysis helped the community consider the likely impacts of land use changes on the budgets of Raritan Township and the two local school districts. This analysis mollified concerns that certain land use changes would create fiscal burdens. With the information from this analysis, Raritan Township was able to develop a mix of land uses that will address community needs while having a minimal net impact on public budgets. Local leaders said that the township would not have purchased such a study on its own, and members of the project team had seen few examples of this type of study being used in this context.

Rapid Turn-Around Visualizations

Participants in the planning process said that the visualizations Glatting Jackson produced during the multi-day design workshops were extremely helpful. Because participants could see their input transformed into designs virtually overnight, they were able to make decisions and move toward consensus more quickly.

Barriers Encountered and Solutions

Trust Building by NJDOT and the Project Team

At the outset of this planning process, the community was generally distrustful of NJDOT. In large part, this distrust stemmed from the long wait for the Flemington Bypass. Delays in a separate intersection project along Route 31 also fueled local resentment of NJDOT and fed suspicions that the agency was not really interested in helping the community.

According to interviewees, NJDOT and its consultants were able to rebuild trust with the community by proving that they were truly interested in obtaining community input for the design of the substitute for the bypass. In addition to public meetings and sessions with the advisory body it created, NJDOT and its project team held many one-on-one interviews with residents and property owners. Also, near the beginning of the planning process, NJDOT completed two small improvement projects on Route 31, which helped convince residents that the agency was truly interested in helping the community with its congestion problem. NJDOT’s eventual agreement to delay construction of the project to replace the Flemington Circle also helped win over local residents and officials. NJDOT’s experience shows that it can take time for a state DOT to build the trust needed for effective collaboration to occur, especially if local opinion of the DOT is initially not very favorable.

Other Lessons Learned

Recognizing Fiscal Realities

Announcing that the Flemington Bypass was no longer a viable project did not earn NJDOT very many friends in Hunterdon County. However, this admission was necessary to get the community to engage in a new discussion about alternative solutions to its congestion problem. As difficult as it may be, it is important for state DOTs to stay engaged with

Fiscal Benefits of Integrated Planning

The traffic modeling for the Route 31 project suggests that the traffic burden on state highways can be reduced significantly if local communities make smart decisions about land use and the local road network. The reduction in traffic on state highways should lead to lower capital costs for the state DOT.

Sources

Origin-Destination Survey Summary Report (Draft), prepared for NJDOT by McCormick Taylor, Inc., January 2005.

Route 31 Land Use and Transportation Plan: Concept Development Workbook (Draft), July 23, 2004.

Route 31 Land Use and Transportation Plan (draft land-use component), draft dated 6/1/07, prepared for Raritan Township by McCormick Taylor, Inc., June 2007.

Route 31 Land Use and Transportation Plan: Market and Fiscal Analyses (Summary of Findings), prepared for NJDOT by Robert Charles Lesser & Co., LLC, January 24, 2006.

Traffic Analysis Summary Final Report for the NJ Route 31 Integrated Land Use and Transportation Framework Plan, prepared for NJDOT by McCormick Taylor, Inc., March 2006 (revised May 2006).

New Jersey FIT: Future in Transportation, About NJFIT, New Jersey Department of Transportation.

New Jersey FIT: Future in Transportation, Route 31 Land Use and Transportation Plan (case study), New Jersey Department of Transportation.

Endnotes

1 Flemington, which is the Hunterdon County seat and its oldest community, is encircled by Raritan Township but is politically independent from it.

2 Resolution 2004-78, Borough of Flemington, New Jersey, adopted June 28, 2004.

3 Hunterdon County Planning Board, Meeting minutes, September 9, 2004.